Honoring Marita Golden: Inside the Mind of A Literary Titan

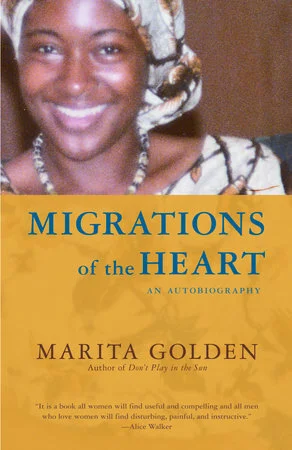

Author, novelist, writer, activist, and advocate, Marita Golden. Photo courtesy of Marita Golden.

By Jaimee A. Swift

A prolific author, novelist, writer, activist, and advocate, Marita Golden is a literary genius whose words and work continue to inspire across generations.

Marita Golden’s interview is a part of our March theme, “Sankofa: Honoring Our Black Feminist Pioneers.” To read the descriptor, click here.

“I write from the center of my experience as a Black woman, and I know that story speaks to everyone and is universal.”

The first book I ever read of Ms. Marita Golden was Wild Women Don’t Wear No Blues: Black Women Writers On Love, Men and Sex, which she edited and was published in 1993. I couldn’t stop reading it––I read the book in a day. I told Ms. Golden how much her words and the words of the 14 other Black women writers whose work comprised the book resonated with me and to that she responded, “You must have an old soul.” While Golden’s assessment about my “old soul” was correct, the reason why her literature resonates with myself and so many others is also a testament to her literary genius and even her skillful mastery to make her words, her life, and her creativity known, heard, and seen. More importantly, Golden’s words resonate because of her intrinsic ability and immense talent to make people feel. In making people feel, think, and ponder on things that have gone unspoken; have been emotionally buried; have brought them joy; and reflect on things longed for, Golden, 69, continues to elicit emotion, consciousness, resilience, and passion through the power of her pen and her words.

Born and raised in Washington, D.C., at a very young age Golden knew she had a knack for writing. This knack––this unique gift––was nurtured by her parents. At age 12, Golden’s mother told her that one day she would write a book. And so far, the bestselling author has written 17 books, the first being her memoir, Migrations of the Heart (1983). Both her nonfiction and fiction explores various themes such as mental and emotional health and wellness in the Black community; the detrimental impacts of colorism; friendship among Black women; cultural identity; and more.

Holding a Bachelor’s from American University in American Studies and English and a Master’s from the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University, as a literary activist Golden founded and served as the first president of the African-American Writers Guild in Washington, D.C. In 1990, she and Clyde McElvene co-founded the Zora Neale Hurston/Richard Wright Foundation, “a non-profit devoted to increasing Black literary representation” with a mission to “discover, mentor, and honor Black writers.” Golden now serves as President Emeritus of the organization.

Having received countless awards for her literature and activism such as the 2002 Distinguished Service Award from the Authors Guild; The 2001 Barnes and Noble Writers for Writers Award presented by Poets and Writers; induction into the International Hall of Fame for Writers of African Descent at the Gwendolyn Brooks Center at Chicago State University; and was honored as a part of the Columbia Heights Heritage Trail in Washington, DC on 14th and Harvard Street NW where she grew up, Golden has lectured, taught, and read her works at George Mason University, University of Lagos, and also served as the Distinguished Visiting Writer in the Master’s of Creative Writing Program at Johns Hopkins University.

Black Women Radicals spoke with Golden about what inspires her to write; how she feels when she sees the current generation of Black writers; her experience growing up in D.C.; and more.

What was the moment that catalyzed your desire to become a writer?

Marita Golden (MG): “Well I don’t know if I chose to be a writer. I was born a writer in that all my life and throughout my child, I was very curious and had a lot of questions about the world. I naturally gravitated to writing as a way of self-expression and inquiry. So I was always having as a child deep and meaningful conversations in my head that evolved my imagination. A lot of kids do that but that doesn’t necessarily lead them to putting all that on paper. For me, it was very important to put questions, to put dreams, my imagining on paper because I knew once I put it on paper, it connected me to other people and it connected me to society. I had my first letter to the editor published in the Washington Post when I was 12 and I worked for the school newspaper in high school. At a very early age, I had a sense of the power of language and the power of the written word and the word shared. Not just the word written in a diary and put away but the word shared––the word thrust into the world. I didn’t necessarily decide that, it was in my DNA. This was also supported by [my] parents, who were pretty amazing people. Not highly educated by deeply literate [and] deeply supportive of what they saw as my gift.”

“The creative process is beautifully mysterious and very often you get called and you report for duty. You do not have to know why. You do not have to know why you are called. You would not be called if you were not capable of fulfilling the call.”

May you please share your writing process? What inspires your writing process? Is it an emotion? A thought? A memory? A sound?

MG: “Often it is a question. A question or a need to––and once again I keep using this word ‘thrust’ but I will use it––thrust my voice into an ongoing conversation. A lot of times, my novels grow out of a question. My novel about an African-American officer who kills a young man during a police stop, that grew out of a question of how does a family survive that? How does a police officer survive that? The book on colorism was inspired ironically by––I got a phone call from my stepdaughter and she said, ‘Oh Marita’––and this was years ago––‘BET has a video you are going to really like.’ I turned it on and it was India Arie and her first song, [which was] the one that got her popular called ‘Video.’ I was so deeply moved by that song that [and] the fact that she had written a song about colorism opened my long many, many decades long desire––she gave me the courage to write about a topic that has been very painful in my life. I wanted [people] to join the conversation that she had started. It springs from a lot of things. A novel will often start with a question. Sometimes, it is a calling. I don’t know why I am writing and that is okay.”

“My last novel, The Wide Circumference of Love, is about a family living in Washington, D.C. impacted by Alzheimer's disease. I had no idea when I started writing why I was writing about Alzheimer’s disease but I spent four years researching and writing and it is now being considered for a possible TV series on HBO and Netflix. But I do not have any connection to Alzheimer’s. The creative process is beautifully mysterious and very often you get called and you report for duty. You do not have to know why. You do not have to know why you are called. You would not be called if you were not capable of fulfilling the call. I stopped worrying about [the process]. I had written about the death of the young man at the hands of a police officer. I had written in the past about very serious subjects, so Alzheimer’s was just another serious subject. I have proven that I am not a person who shrinks back because the topic was hard. That was why I was writing about Alzheimer’s. People always ask, ‘When you were writing about Alzheimer’s was there someone in your family that…’ and I respond, ‘No, no, it wasn’t anything like that. I just got the call.’ I turned out to be a perfect––not the perfect––vessel for the story because I have always felt...so as someone who came of age during the sixties and got ‘Black’ and got proud, confirmed a lot of things my father told me. I grew up in a household where my father was Afrocentric. I grew up on stories on Sojourner Truth, Cleopatra, and Hannibal. I went to college in the sixties, which was an amazing time to become a young Black person in America. So these stories infiltrated my sense of what I was going to do as a writer. Because I knew all that––the story of being a Black person in America and an African-descendent in the world––was a valuable story, I knew I was going to tell that story. I wasn’t going to apologize for it and it was universal. My sense of ‘our story’ as meaningful, when I actually think about the roots of that idea, were seeded probably in my childhood by my parents and I just kept growing it, growing it, and growing it as a writer.”

“The fact that those women mentored me meant a lot to me and it meant that I have spent my life mentoring other Black writers.”

“The other thing is that I was very lucky because I was mentored by amazing people like Audre Lorde and June Jordan. When I was in New York in the seventies, when the world had started to break open in a meaningful way for Black people; to be young, gifted, and Black in New York City in 1972. I went to a poetry reading where Audre Lorde was reading her poems. At that time, I was writing poems and I was not writing any fiction or anything like that. I was writing poetry and some journalism. I gave her some of my poems and asked if she would read them. And she read them! She called me on my phone because you know there was no email! [Laughs] She called me on my phone and said, ‘You are a wonderful writer. Keep writing.’ Then June Jordan read some of my work. The fact that those women mentored me meant a lot to me and it meant that I have spent my life mentoring other Black writers. My literary activism with first, the African-American Writers Guild, and then the Zora Neale Hurston/Richard Wright Foundation, is a literary but also a political act. So when I really think about all the influences I had like my parents and then these women who were getting their props and recognized as important, but they took the time to mentor unknown people and help us become known.”

You are the co-founder and founder of the Hurston/Wright Foundation and the African-American Writers Guild, respectively. How does it feel to see this new generation of Black writers and the work they are producing? What advice would you give to Black writers today?

MG: “It is very satisfying. I will say in terms of the Foundation, it was born out of my deep desire to be in community with other Black writers and to create a community that would be supportive of us. I think at this point it is deeply satisfying to me that the co-founder, Clyde McElvene and I, were able to create an organization that was so powerful, so seductive, and so efficient in what it did that when we knew that our time was over and it was time to turn it over to a new generation of leadership, that new generation of leadership stepped forward. It is really amazing that a small Black organization that started 30 years ago is still going strong and has a whole new generation of people leading it and has really helped to nurture two generations of some of our most important young Black writers out there. I feel enormously proud of that. I am deeply satisfied that a new generation is taking it over. It is important for us as leaders to nurture a new generation and step aside. I don’t believe in that school of leadership where you stay on and hang on forever. I don’t believe in that. I think that is something that has hampered our community.”

Author, novelist, activist, and advocate, Marita Golden. Photo courtesy of Marita Golden.

Why is it important that Black women writers are seen as key leaders and agents of the Black radical literary tradition?

MG: “Well, it is important that they are acknowledged because as women, our texts and our stories have been marginalized and defined by everybody but us. That is why the groundbreaking work that was done in the seventies was so important. Like the anthology, The Bridge Called My Back and the other work a lot of Black feminists and Black lesbians were doing was really, really, really and very, very, very important. It is important because when we talk about this issue of inclusion––which is a word I despise and diversity, which is another word I despise but I will use them––that has to be the default setting. It is not like you are ‘including’ Black feminists or you are ‘including’ Black lesbians because you are liberal and you want to check off something but you are not telling the entire story if you do not include their voices. If you are not telling the whole story, you are not telling the story. You are imitating. You are mimicking but you are not telling the story. So the whole history, for example, of this country is that each generation of people who have been left out are pushing to tell the story And boy, we are a lot closer to telling the story than we have ever been. So it is not even a matter of why it is important. It is inevitable. It is necessary––it has to be. Without it, you don’t have anything. We don’t have to value judge it. Without those stories, you are not telling anything worth hearing.”

What has been the most rewarding moment or moments of your career?

MG: “Writing my very first book was very satisfying because it was a memoir. I had to sit down at the age of 29 or 30 and write a book about my life. That meant that I had to accept the idea that this story of this young Black woman coming of age, getting ‘Black’, and finding out what she was and what she wasn’t and what she could be in the world, was a story that was deeply meaningful not just to me but a story that could be deeply meaningful to other people. Writing that book was one of the most important moments for me as a writer. My cultural literary activism has been very important. The African-American Writers Guild and the Zora Neale Hurston/Richard Wright Foundation––my literary activism took a lot of my time but it took a lot of my time because that is what I wanted to do. I mean it was a passion––an obsession. Probably, the third thing would be is having people read my work and actually tell me that they were deeply moved or changed or impacted by my work. Probably those things.”

You were born and raised in Washington, D.C. and you have seen how much the District has changed. Can you speak about some of your most memorable moments growing up in D.C.?

MG: “Well when I was growing up here, it was really ‘Chocolate City.’ It was a funny reality because one hand, we didn’t have political power. I grew up in a time where there was no mayor and Congress completely ran the city. By the time I was a teenager, we could vote for the mayor. There was a time when we couldn’t even vote for the president. I have seen throughout my lifetime the gradual growth of more political autonomy but at the same time, we don’t have full representation so we are still essentially a colony. Culturally, it was very rich because it was a Black city but at the same time, there was an awareness that segregation was real. Within the Black community, of which I was a part, that community was a very––I never felt the absence of anything. I never felt that I couldn’t go into certain parts of the city or I wasn’t welcomed there or that I didn’t have anything. I felt the Black community I was a part of was very rich and very nurturing and very supportive. What happened to D.C. now is a part of a global trend of capitalism that is transforming cities and widening economic inequality. It is not just happening in D.C. but it is happening all over the world. That is just a part of the way capitalism is developing and devouring at this particular time. Just as African-Americans are losing political power in this city, you see where our power is threatened on a national scene. You see the power of people of color being turned back all over the world––Honduras, Guatemala, for Indigenous people like in Nicaragua or Venezuela. All the socialists who gave Indigenous people their first taste of power, that is now being turned back. We are just a part of a global trend.”

Who are Black women who inspire or have inspired you?

MG: “First, Zora Neale Hurston. I would have not named the Foundation after her if she had not been a powerful inspiration. She is an inspiration to me because I love her insatiable appetite for living, for life, her insatiable love for her people, her daring––she was just incredible. It was like the longer she had been dead, the more we discovered of what she did. You know like Barracoon and I think there is a book coming out later this year about more and more of her writing. She was just a powerful inspiration for me being a woman of letters because she wrote in so many different genres. Some people will say, ‘Oh, but her politics’; well, she had a certain attitude about Black people and Black empowerment based on the fact that she came from an all-Black Southern town and that was her view. I think she was a powerful inspiration to me. The more and more I read about her life, the more I found her to be an inspiration in a lot of ways.”

“The woman does not have to be famous to inspire me. There was this Black woman––I don’t know if you read about this––but she was an 82-year old Black woman who was a bodybuilder and a guy broke into her apartment and she picked up a chair and beat the crap out of him! And she said she wasn’t going to press charges because she sent him to the hospital! [Laughs] She is an inspiration because she is keeping her body and her mind in good shape. My mother was an inspiration to me. I will definitely say Zora Neale Hurston because she wrote about a lot of things––she wrote about colorism before a lot of people did. She was just pretty amazing I think. I find Black women inspiring in general; Toni Morrison, too. I think for me both Morrison and [Alice] Walker taught me that you could be brave enough to write really hard stories. Alice’s stories were full of violence and tragedy and you can do that as a Black woman and you can get the nerve up to write these really hard stories. What Morrison taught me was not so much about writing but speaking; that you can define who you are and not back down from that definition.”

“A Black woman who is awake. Truth be told, radicalism is the default setting for most Black women who have changed their communities and changed America.”

What does a Black Woman Radical mean to you?

MG: “A Black woman who is awake. [Laughs] Simple as that. A Black woman who is awake. Truth be told, radicalism is the default setting for most Black women who have changed their communities and changed America. I think about Rosa Parks. She was radical. When you really know the story of her and her real life and her real activism, she was a radical. I think when you really look at the lives of women and people who really changed the culture and the society, radicalism is where they start because they know that the society is radically corrupt at its core, so the only possible response is radical progressivism. When you deal with a society that is radically evil and corrupt at its core, which is what America is, and we have changed some of it but it still remains because of capitalism and all of that, but the only real response you can have is not gradualism––not Barack Obama––but radicalism. I think that is what women know; that is what Black women know. That is why it took Black women in the sixties to pave the way for White feminism. That is why it took for Frederick Douglass to teach Susan B. Anthony and her friend the intersectionality of racial progress and women’s progress. So, Black people are the original radicals.”

For more information about Marita Golden and her literary works, please visit her website.