“Machismo Will Never Be Fucking Revolutionary”: On The Radical Rebelliousness of Denise Oliver-Velez

Political activist, feminist, journalist, community organizer, anthropologist, and member of The Young Lords Party and the Black Panther Party, Denise Oliver-Velez. Photo Credit: John Buckley and Voices of New York.

By Jaimee A. Swift

A powerhouse political activist, feminist, journalist, community organizer, anthropologist, and the former Minister of Economic Development of The Young Lords Party and member of the Black Panther Party, Denise Oliver-Velez is still and will always be radical, rebellious, and militantly Black.

Denise Oliver-Velez’s article is a part of interview is a part of our March theme, “Sankofa: Honoring Our Black Feminist Pioneers.” To read the descriptor, click here.

“I’m black.

I’ve been black, and proud to be black, my whole life. My parents raised me like that. They grew up as ‘Negroes.’ They had to drink at water fountains labeled ‘colored.’ They lived long enough to become Afro-Americans, and then African Americans.

I was, and still am, militantly black.”

Bold and brazen, Denise Oliver-Velez, 72, will not bite her tongue when it comes to injustice. And it is because of her radical rebelliousness and unwavering determination and dedication in the fight for justice and liberation for all oppressed peoples that Oliver-Velez is recognized as one of the most formidable activists and leaders of our time.

Active in several social movements such as the Civil Rights Movement, women’s movement, and HIV/AIDS activism movement, Oliver-Velez was a member of the Young Lords Party in New York. However, the Young Lords was originally a Chicago-street gang turned radical, Puerto Rican political organization founded by activist José "Cha-Cha" Jiménez in the late 1960s. The organization’s mission was to fight for socio-political and community empowerment and liberation of Puerto Rico––liberation of the island and inside the United States––and all Third Word people. As the children of Puerto Rican immigrants, the Young Lords––originally the Young Lords Organization and later, the Young Lords Party––built a national grassroots movement in the barrios of the United States.

The Chicago Young Lords formed after Mayor Richard J. Daley evicted and displaced Puerto Ricans and other Latino and low-income housing communities to establish an inner-city suburb in Lincoln Park. Influenced by the direct action campaigns and initiatives of the Black Panther Party and as a member of the Black Panther Party’s Rainbow Coalition led by Fred Hampton, the Young Lords addressed the stark racism and discrimination Puerto Ricans faced in Chicago such as lack of access to proper housing, education, employment, healthcare, and police violence. Occupying the McCormick Seminary and staging a sit-in at Chicago’s Grant Hospital to demand free medication, X-rays, and equipment, the Chicago Young Lords also trained youth and students as leaders to rally the Latino community at the national level.

Organizing neighborhood clean-ups and providing free community services, a chapter of the Young Lords was chartered and established in New York by students from SUNY-Old Westbury, Queens College, and Columbia University in 1969, where Oliver-Velez was one of the founders. Tired of the inequities that pervaded Puerto Rican and low-income neighborhoods in New York, the Lords led actions such as the “Garbage Offensive”, where they lit garbage on fire in protest of the prejudiced and discriminatory refusal of the New York City Department of Sanitation to pick up and clean garbage in their communities. In 1970, the Lords barricaded the Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx and demanded proper medical treatment for the community and with this, widely changed how the hospital served and provided healthcare access. Eventually splitting with the Chicago Lords, the New York Lords also established Palante, the official bilingual newspaper of the Party.

Like the Black Panther Party’s 10-Point Program, the Young Lords had a 13-Point Program, which was written in 1969. However, one of the points emphasized “revolutionary machismo”, stating: “We want equality for women. Machismo must be revolutionary...not oppressive.” Tired of the rampant sexism and sexual discrimination within the Party, where male members would relegate women to menial tasks and responsibilities such as secretarial work and child care and refused to appoint them to leadership positions, Oliver-Velez and other women members demanded that the Central Committee of the Young Lords give full inclusion to women. Because of Oliver-Velez and other members’ activism, the 13-Point Program was revised in 1970, with the new point being: “We want equality for women. Down with machismo and male chauvinism.” Oliver-Velez was later appointed as Minister of Economic Development and became the highest ranking woman in the Party. In her position, she was integral in spearheading women’s inclusion, writing, and production of Palante, where Oliver-Velez and others published the Young Lords Party Position Paper on Women in September 1970.

Always at the center of the Lords’ mission was the liberation of Puerto Rico and their main slogan Tengo Puerto Rico En Mi Corazón (I have Puerto Rico in my heart), showcased that. However, after the Young Lords voted to physically transition its headquarters from New York to Puerto Rico, Oliver-Velez quit the Young Lords and became a member of the Black Panther Party. Here, she worked on the local Panther Party paper and did extensive international travel and solidarity work. Later, Oliver-Velez established herself as a pioneer in media, where she became the executive director of the Black Filmmaker Foundation and was a co-founder and program director of Pacifica’s first minority-controlled radio station, WPFW-FM, in Washington, D.C. She also published ethnographic research on HIV/AIDS and co-wrote, with Iris Morales, the foreword to The Young Lords: A Reader (2010), edited by Darrel Enck-Wanzer. An Iyalorisha Yemaya, Oliver-Velez was also an adjunct Professor of Anthropology and Women’s Studies at SUNY New Paltz. She is currently a contributing editor for the Daily Kos.

With all of the work that Oliver-Velez has done and continues to do, it is no wonder she is one of the most important Black women leaders of our time. And it is also no wonder why she is still and will always be radically rebellious and “militantly Black”.

Oliver-Velez spoke with Black Women Radicals about what led her into her activism; how her family was already involved and ingrained in radical politics and organizing; why it is important Black women have strong Black women role models; and what advice she would give organizers today.

What initially led you to join the Young Lords Party and the Black Panther Party? What led you into your activism?

Oliver-Velez on the early years of her life and budding activism

Denise Oliver-Velez (DOV): “Well, the Young Lords was sort of serendipity––well, let me go back. I was politically active before then and I grew up in an activist family, so it wasn’t as if I opened my eyes and said, ‘Let me go off and join something!’ [Laughs]. I don’t know what life is like as a non-political person because as I said, I grew up surrounded by people, who I guess the appropriate term these days [would be considered] the ‘Left’. My parents’ friends and everyone that was close to them were Leftist or fellow travelers or Communists or whatever because if you know the history of the Harlem Renaissance and the people in the arts, [they] were pretty political. My dad was an actor, so I was surrounded by folks like Paul Robeson and that whole crew. I don’t even understand what it is like to be from a family that isn’t political. I had that particular kind of privilege, I guess. When we talk about class privilege and white privilege, I also think there is a political privilege to grow up around activism. That was my norm rather than something that was outside of myself. As a very young person, I think I was in the third grade and I remember refusing to get under my desk because the Russians were going to bomb us. [Laughs] That was during the McCarthy period. Myself and two other little girls in my class in grade school, who were also red diaper babies, we [and other students were] forced to get under our desk to survive the bombing [and] they handed us dog tags to wear so our ashes could be identified. The three of us refused to get under our desks and we refused to wear the dog tags! [Laughs] How many third graders do you know who are part of protest movements? Because I was! [Laughs] The teacher was very upset but then I went home and told my parents and my dad was furious and went up to the school and said, ‘How dare you push this anti-Soviet propaganda on my daughter!’ [Laughs]

“I got a chance to meet Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer when she came to New York. That kind of blew me away. She was a towering figure––just amazing.”

“By the time I was in fifth grade or maybe younger than that, I protested anti-Semitism when I was six or seven years old, when I was in brownie troop at Penn State. My dad got involved in standing off the Ku Klux Klan when he was a teacher at Southern University in Baton Rouge. I think two years after that, there were shootings on campus but he was one of the young, radical professors, for which he lost his job. We moved back to New York and moved out to Queens and there was a race riot when I was bused into a new junior high school. I joined the local NAACP youth group and we did sit-ins. I went to probably one of the more radical high schools in New York––I think it is called LaGuardia High School now. The teachers were progressive and the students were all involved in anti-war movements and ‘Ban the Bomb’. Some of the students who were a little older went down South to participate in Freedom Summer––my mother wouldn’t let me go. In 64’, I graduated and went to Hunter campus in the Bronx––it is now Lehman College. I got involved with the only activism on campus at the time because there were only like four Black students and one Puerto-Rican. Anyway, I got involved with integrating the campus service sorority and I got a chance to meet Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer when she came to New York. That kind of blew me away. She was a towering figure––just amazing. I decided I didn’t want to be at Hunter College in the Bronx surrounded by White people anymore [Laughs]. I went home and told my mother, ‘I want to transfer and go to Howard!’ And my mother said, ‘That’s nice [but] Hunter is 48 dollars a semester so I suggest you better get a scholarship if you want to go anywhere!’ [Laughs]. Mothers are practical like that.”

Denise Oliver -Velez from the Revolutionary Peoples' Communications Network in front of Reverend C.K. Steele's church during visit to Tallahassee, Florida. 1971. Photo Credit: John Buckley. Public Domain.

Oliver-Velez on transferring to Howard University and meeting members of the Real Great Society (RGS)

DOV: “But I did get a scholarship and I went to Howard, which was a completely different experience than going to an all-White school in the Bronx. When I got to Howard, I gravitated toward the political people on campus and not the most socially oriented folks because you know, Black colleges can also be pretty bougie. Hanging around at the time with organizing students, there was a brotha and his partner, Hubert “Rap” Brown and Linda. I gravitated towards them and got involved with some of the movements that were developing at that time like the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and ideas on armed self-defense. That made a lot of sense to me––armed self-defense––because my family was very militant coming out of slavery. My great-uncles and great-aunts were all armed and they all stood off the Klan. I grew up and was raised on those kinds of stories of strong men but also of strong women. I think that is so key––to have role models within your family and even outside of your family who are women of strength. Growing up, my mother would tell me she would get up during the middle of the night and go to the bathroom and she would run into Aunt Martha who raised her, who was creeping around the house barefoot with a shotgun to catch burglars. These are the sort of, I don’t know––do you have family mythologies? These were the types of stories I was brought up on. It never occured to me that women should be passive or women shouldn’t stand up for their rights or for self-defense because that was what I knew.”

“That made a lot of sense to me––armed self-defense––because my family was very militant coming out of slavery. My great-uncles and great-aunts were all armed and they all stood off the Klan. I grew up and was raised on those kinds of stories of strong men but also of strong women. I think that is so key––to have role models within your family and even outside of your family who are women of strength.”

“At Howard, I got involved with a group of students who ultimately shut the school down and took over the campus and sat down to demand––at a Black school––a real Black president of Howard [University] and Black Studies. While I was there, I got to know a very militant brotha who was a Black Puerto Rican and who was in the architecture school, he and his wife. They had invited some Puerto Ricans from New York to come to Howard for something they were doing. He said to me, ‘I know you are from New York and I know you are familiar with Puerto Ricans and you hang out in the barrios, I need places for these brothas to stay. Can some of them stay at your apartment?’ I said yes and that is how I encountered the brothas who had been part of the street gang on the Lower East Side and had become an anti-poverty agency called the Real Great Society (RGS). They were kind of stunned when they stayed at my house because they were like, ‘Is that a shotgun by your door?’ [Laughs] They were like, ‘Is it a real one [and] why do you have it?’ I said, ‘Well, to shoot rats that are in the backyard when I need to take out the trash but [also] if someone tries to come in and break into the apartment, I will just take the gun and point it at them and tell them to get the fuck out of here! [Laughs] They were blown away because it was not a female kind of thing. They were like, ‘This sister is deep.’

“They also said to me that whenever I was back in New York and needed a job to come and see them. I left D.C., came back to New York, and I remembered these brothas and went to visit them at the Lower East Side at the Conference Square Community Center. They offered me a job as a vista volunteer––you know, like the internal peace corps––and they sent me up to East Harlem. They had bought buildings that they were renovating and they set up a prep school for kids who had been thrown out of all the traditional schools in New York. I was hired to teach at the prep school. While I was there, along with another couple of people who were a part of the initial founding of the Young Lords, there were also people from RGS. We got recruited to go out to this experimental college that was being set up on Long Island––the Old Westbury. My mother was on my case and asking, ‘Are you ever going to finish school?’ [Laughs]. You know how mothers are! She was like, ‘How dare you not get a degree?’ I wasn’t even thinking about a degree. [Laughs]. I was working in the community.”

Oliver-Velez on her experiences at Old Westbury and founding the New York Young Lords

DOV: “But anyways, the Old Westbury offered me all my expenses paid, tuition, housing, room and board, and a stipend. I called my mom, because I used to call her on the weekends, and said, ‘These people here want me to come to school for free’ and she was like, ‘Take it! Go finally get your degree!’ So, I went. The brotha that I was with at the time and a couple of people from RGS, we all went out to Old Westbury. There were only 95 students and there were only 16 students of color. There were not enough of us to form a Black caucus or a Latino caucus or any kind of caucus, so we called ourselves the ‘non-White caucus’. When I think about it now, it was sort of defining yourself as not the norm. All 16 of us became the non-White caucus and were pushing to get more students of color on campus and professors of color. We ended up recruiting one of the first Black anthropologists, Council Taylor and a Panamanian brother, Dr. Carlos Russell. That was the year Ocean Hill–Brownsville broke out. The very powerful teacher’s union was opposed to the community control of schools. Black and Latino parents had demanded that they should have control of their kids’ education. They got into a huge beef with the teacher’s union and it wound up with the teacher’s union going on strike. The college took a bunch of us to keep these schools open in support of the Black and Puerto Rican families who were fighting for their kids’ education. It was the first time I ever crossed a picket line because my family was union. My mom was in the union and in fact, she gave me money and she said, ‘You go on and you keep these schools open’ and I said, ‘Mom, I am going to have to cross the picket line.’ And she said, ‘You betta go!’

“I read stories about this history––those of us who were women, a key part of this group on this campus, were erased. It was like we didn’t exist. I am always stunned. It is like, ‘Well, the guys went off and formed the Young Lords.’ Hello?! There were women involved. It was just we were not stupid enough to get in this damn car.”

“There was [a lot] of political activity going on at the campus. Two of the members of the non-White caucus, a brother named Paul Guzmán, who became Pablo Yoruba Guzmán, and a brother named Bob Bunckley, who changed his name to Muntu, had been going into the city and had been hanging out at the Panther office in Harlem. They came back to campus with a copy of the Panther paper and in the paper was an article about the Rainbow Coalition, Fred Hampton, and this group called the Young Lords in Chicago. They were––we were––all taken with it and since a number of the people were in the non-White caucus were Puerto Rican––well, not everyone was. Quite a few of us were African-American. Well anyways, they decided to go and visit this Cha Cha guy [José Cha Cha Jiménez]. They had this raggedy car and us sistas, having good sense, were like, ‘We are not riding in that car going all the way to Chicago. Y’all are crazy.’ It was only brothas that went. I read stories about this history––those of us who were women, a key part of this group on this campus, were erased. It was like we didn’t exist. I am always stunned. It is like, ‘Well, the guys went off and formed the Young Lords.’ Hello?! There were women involved. It was just we were not stupid enough to get in this damn car. So, they came back and said, ‘Well, Cha Cha just made us the New York Young Lords.’ That is how it happened. It’s not like I got up one morning and decided, ‘I am now going to join the Young Lords’, you know? It was organic. It just occurred.”

Denise Oliver-Velez marching in the Puerto Rican Day Parade, 1970. Photo credit: Michael Abramson.

Oliver-Velez on the position of women in the Young Lords Party and challenging “revolutionary machismo”

DOV: “There had been some other people visiting Old Westbury from some of the other student organizations in the city. One was Juan González––I think you know Democracy Now, the show? Well, Juan was one of the student-activists at Columbia [University] at the time, which was the birth of a lot of the SDS kind of stuff. There was another student from Queens College, who was in the SEEK program. Those were the programs to bring Black and Latino students on campus. His name was Felipe Luciano. We connected and that became the core group [of the Young Lords]––they also hooked up with a gang from the Lower East Side. Ultimately, it became a decision: do you stay in school and finish or do you throw yourself into becoming a Young Lord twenty-four hours a day? Or twenty-five hours a day, we used to say. Of course, being who I was, it was like, ‘Fuck school!’ [Laughs]. The next thing you know, I am in East Harlem again. My mother was really not happy but too bad. [Laughs] My father just said, ‘She’s going to do what she is going to do. All power to the people!’ So, it was the genesis of my being a part of the founding of the Young Lords. Initially, the women in the organization were no different from the men and were engaged in all kinds of things, which were modeled after programs of the Black Panther Party. We actually had a very close relationship with the folks from the Panther office in Harlem. We were involved in joint programs with the Panther Party and we set up free breakfast programs like the Panther Party. We were also part of the Bronx Housing Coalition dealing with the bad housing and tenant organizing and we were focused on the issues raised in the community, a lot of them related to people’s health. We didn’t have terms at the time like environmental racism or reproductive justice but we were doing those kinds of things. As we got more involved in the daily work of the organization and more women got involved, it was kind of interesting because the way shit came down, a lot of the daily work of running the organization fell down on a lot of the sistas. The leadership of the organization was all male.”

“It was structured as a paramilitary group with a Central Committee––this is taken from the Black Panther Party––and then you have ministries, so the Defense Ministry, the Health Ministry, [and] the Education Ministry. At one point when they were putting together the Central Committee, they were like, ‘The Panthers have a woman––a communications secretary.’ They were talking about Kathleen Cleaver. One of the brothas said to me, “Do you want to be the communications secretary?’ I said, ‘No, I can’t type’ but I was lying! [Laughs]. I had made up my mind––somewhere in the back of my head I didn’t want to be placed in a position where the only thing I am doing is typing shit. I wanted to be actively out doing stuff in the street. They wound up giving me a position like a sergeant in the military called ‘Officer of the Day.’ I had the ability to hand out discipline and we used to give discipline to people. If you were late, you had to give me 100 pushups or run around the block. If you really fucked up bad, you had to go to study hall and stay up all night and write out dissertations about Lenin or some other person. Then you are sleepy because you didn’t get any sleep and you have to get up at six o’clock in the morning and take these kids to the free breakfast program and then you got to sell me 100 newspapers. I was the only woman to have this form of power within the organization. I didn't think about that then but when I look back on it, I see it now. And I used it. I had no problem if someone from the Central Committee came in and I thought they fucked up, I would give them discipline. People were like, ‘You can’t do that––he is the Chairman!’ and I was like, ‘I don’t give a shit!’ [Laughs] A lot of the younger sistas kind of looked up to that in a way. And when I say younger, okay––we were the Young Lords. Those of us who were older, the elders in the organization, were like 21 or 22. The youngbloods and the young sistas were 15 and 16. When you are that age, a 15-year old and a 22-year old might as well be two generations apart. So, us old folks formed pretty much the leadership in the organization and we had young women who came into the organization who had never been in any kind of group––at all. They didn’t have a background in politics and they were learning.”

From the left Iris Morales, Denise Oliver, Nydia Mercado, and Lulu Carreras. Photo credit: Michael Abramson. c. 1970

“As more women came in, ultimately shit happened. Things went down. We started having––the apartment I lived in, we lived in collective apartments. I was with two sistas in an apartment that was right around the corner from our main office. The only time we had free time was on a Sunday but we started holding meetings––just women––on Sundays. One, we were doing our own political education––we called it ‘PE’. We were talking about historical women and their role in their various movements. It wasn’t just Puerto Rican women-–we looked at Black women, women in Vietnam. We all looked up to a woman who used to come around and support us, Yuri Kochiyama. Yuri is the woman––Malcolm died in her arms. Yuri was kind of like a mom to us. We looked up to her and we were studying all kinds of things. We were also pissed at all the things that were going down internally in the organization. You also have to think about the fact that we were young people. I say this to my students, ‘You know we were young people! We had hormones. We weren’t always like, ‘All power to the people!’ and marching with our berets all the time.’ We also had ‘SO’s’––significant others––whether it was a male person or female person. We also had gay women in the organization as well. We had stuff we would hash out.”

“I guess in some ways, it was parallel to some of things that were going on in the women’s movement, which was developing at that time, where they had consciousness raising sessions and whatever; except we weren’t just sitting around raising our consciousness––we were confronting issues that were in front of us and our thoughts around issues. We developed probably one of the most important political platforms on reproduction and reproductive justice differing from the rest of the Left. Feminists were anti-abortion and we were so far beyond that. We were like, ‘Women should have a right to an abortion but women should have the right to have as many kids as they want and be able to feed them and be able to have them and to be able to get child care.’ That is more like some of things that were developed by groups such as SisterSong. I want to say to you that out of all the radical organizations at that time, we were first. It grew organically in understanding the needs of some of the sistas in the organization who had kids and looking at that as part of the reality. We also knew what had happened in Puerto Rico with the sterilization of a third of the women on the island. We were looking at sterilization as a form of genocide but on the other hand, we were looking at the fact that women should have a right to control their own bodies. We never put people in the extreme feminist position at that time of saying, ‘Oh, you know, children are a burden or whatever’ because children are a part of our community.” At the same time, Fran [Frances M. Beal] had formed the Black Women’s Alliance, which she later changed to be the Third World Women’s Alliance. One of the key sistas in that organization is somebody who I grew up with in Queens, when I moved out there. We had been invited to the early meetings of what became the World Women’s Alliance and Fran had put out Double Jeopardy––which is a key piece of literature. [Fran] had invited us––she and Keisha and some of the other women––to leave the Young Lords and become a part of the Women’s Alliance. And the thing was it was an interesting offer. It was tempting in some ways because you could be with women and not deal with bullshit from brothas! [Laughs] But we said no. We said, ‘We will support you and understand your need to be separtist as a collective of women but we feel it is our responsibility as a community that includes men––your sons, your nephews, and your uncles [and] to feminize them. And we will continue to do that work.”

“But what we did do when we were confronted with a hairy situation––the [Lords] wanted to make an alliance with a nationalist group that treated women, as far as women were concerned, very poorly. We got together––the women in the organization and some of the young brothas we worked closely with, not the the older ones––but we demoted the entire Central Committee and we set up a list of demands. One that the program and platform of the organization be changed because said––and it was obviously written by a man [Laughs]––that ‘machismo was revolutionary.’ We were like, ‘That is an oxymoron. Machismo will never be fucking revolutionary.’ [Laughs] We had that changed. We demanded there be women on the Central Committee in leadership and the Central Staff––they were like lieutenants and they served as the second staff of leadership. I got put on the Central Committee and a number of women were made leaders of different ministries. Later, another woman was put on the Central Committee.”

Oliver-Velez on women’s inclusion in Palante, the Young Lords’ newspaper

DOV: “We also dealt with the newspaper and demanded that at least half of the articles in the newspaper should be written by women or be about women’s issues. A lot of the underground papers––I call them underground because it is not mainstream media. Every organization had a newspaper. The Muslims had Muhammad Speaks; there was the Panther paper; there were papers like the Rat, which was all male and then women took it over. Remember: this was a time where there was no Twitter, no Instagram, and there was no internet. The way we could communicate was vis-à-vis putting out a paper and going out and physically putting up posters in neighborhoods. You all in your generation these days have so much ability. I mean the technology you have is mind blowing. The ability to use it––some shit goes down in San Francisco, you know about it in five minutes on Twitter. We did not have those kinds of options. We had mimeograph machines––my students don’t even know what mimeograph machines were [Laughs]. That was it. It was really important that our sort of propaganda vehicle be up and functioning because we used that to educate people in the community and keep them in touch with stuff that was going on. It was really important that that organ, the Palante paper, covered issues and had things written by women. “

“When you have something, women need to be key in running shit and training other women to move up and to get those skills and to be confident in those skills because so much in our culture mitigates that.”

“Most of the publications that were out there on the Left––and I say that broadly––were male dominated. It makes a difference when it is women writing, when you have women’s voices, and when you are training women to lay out the paper and be a part of the production of the paper. What I have learned from the Lords is something I have carried with me in every endeavor I was involved in after that time––whether it was building a community radio station where I became the first Black woman program director of a public radio station. I ensured we had women on staff running public affairs and doing whatever but also women who were doing the production and women who were engineering. Later, at the Black Filmmaker Foundation and when I worked for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, it is something that is, I don’t know, the way I think [Laughs]. When you have something, women need to be key in running shit and training other women to move up and to get those skills and to be confident in those skills because so much in our culture mitigates that.”

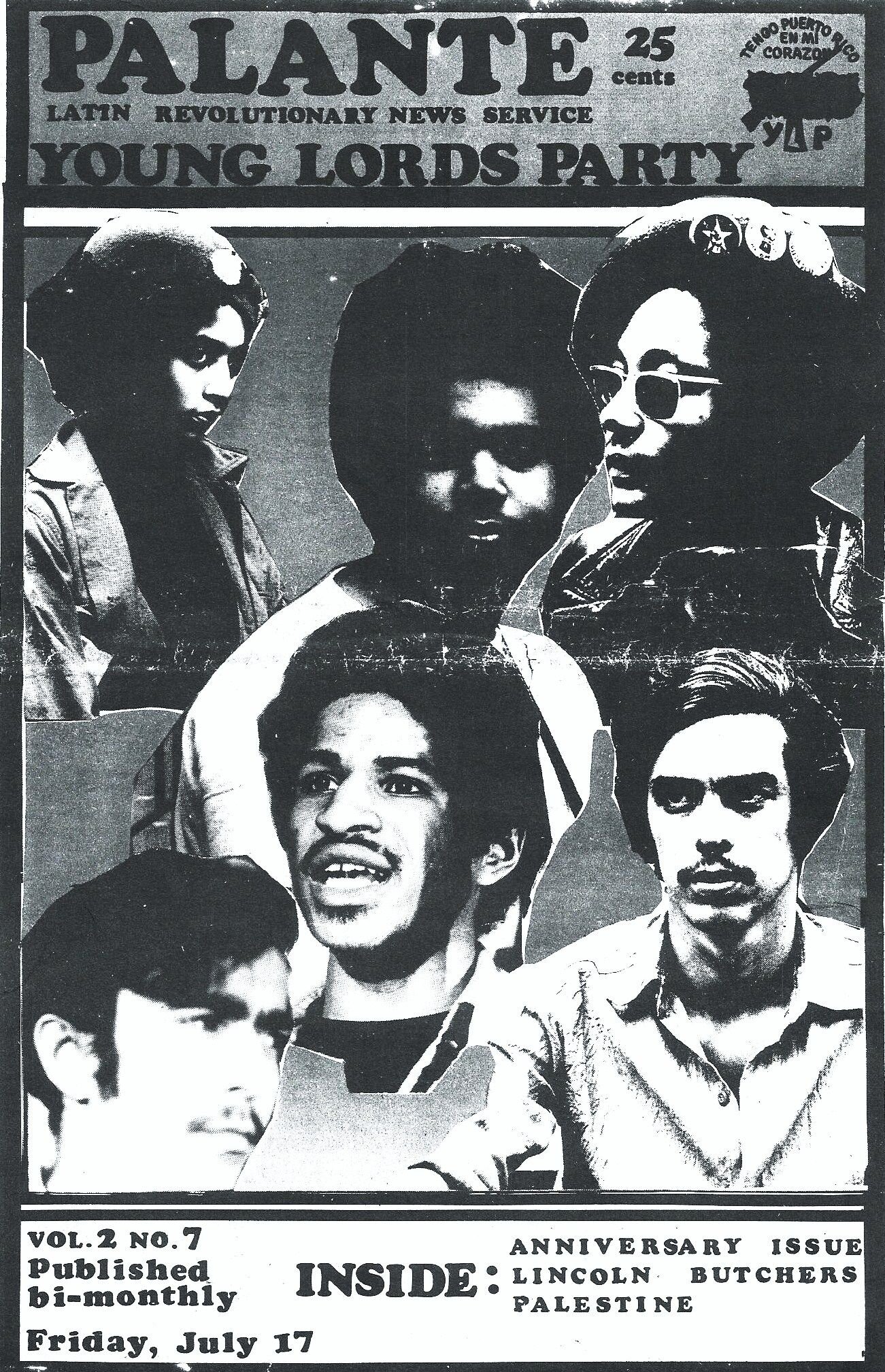

Cover of Palante newspaper.

Oliver-Velez on asserting her proud African-American identity, the demise of the Young Lords Party, and her work as a member of the Black Panther Party

DOV: “Some key issues went down in the Lords in what direction the organization was going to move in. One thing I have to stress is that people see the Young Lords Party as Puerto Rican but a third of the members of the Young Lords Party were African-American. I am always having to correct somebody on the internet when they say to me, ‘You’re Puerto Rican’ and I am like, ‘No, I am not’ and they are like, ‘Oh yes, yes you are!’ [Laughs] And then I am like, ‘No, I am not. Not one drop.’ Then I tell them in Spanish, ‘No tengo sangre boricua’ and they get all confused. I am like, ‘Hello?!’ If you grew up in New York and grew up in neighborhoods, I learned Spanglish just like everybody else. I will see on the internet and they will say, ‘Afro-Latinx Denise Oliver’ and I will say, ‘Nope, can you change this please?’”

“So anyway, the organization was at a critical point in its development. One day the Central Committee decided they wanted to move the entire operation of the Young Lords to Puerto Rico because one of the issues in the platform and program was liberation for Puerto Rico. I objected vehemently. I said that it wasn’t going to work and that it didn’t make any sense. You don’t abandon your base––when you build a base, you stick with your base. Puerto Rico has its own political organizations and structures and we had come in contact with them. We made trips to Puerto Rico and met with the Puerto Rican Independence Party. I knew from my trip there that it wasn’t going to work. I argued against the move and so did several other people from the Central Committee. Ultimately, a vote was taken and the decision was made to move the organization to PR. And I quit [Laughs]. I walked 15 blocks to the Panther office and saw all these people I already knew because we were working very intimately together on things. And I said, ‘I am here! I am joining you!’ [Laughs] They were like, ‘Well wait, what happened?’ and I am like, ‘They want to go to Puerto Rico. That shit ain’t going to work.’ And then I became a Panther.”

“The East Coast of the Party was putting out a local Panther paper and I went up to the Bronx office to work on that. I got involved in other things but then one day, the phone rang. I got orders to go to the international section and I was there for a while. I got to travel with Kathleen [Cleaver] and got to do some international work. By the time I got back, there was a split in the party, which people described as the ‘Huey P. Newton and Eldridge Cleaver split’ but actually it wasn’t. It was a split between the East Coast and the West Coast because I was there when the press release was written. And so, I became a part of that East Coast contingent and put together the newspapers they put out. And then a whole bunch of other shit went down and everybody had to go underground and run from the feds for a certain period of time. During that period of time, some of my closest friends were killed by the whole COINTELPRO crap. That was kind of the end. See, you asked me a simple question about how you joined the Young Lords and the Black Panther Party and you get a dissertation!” [Laughs]

Denise Oliver-Velez, left, and Kathleen Cleaver, right, leaving airplane during a visit to Tallahassee, Florida. Photo Credit: John Buckley. November 26, 1971. Public Domain.

You talked about meeting Fannie Lou Hamer and how she was such a towering figure to you. Do you ever think people like me and countless others consider you to be the same way?

DOV: “Every once in a while people say something like that to me. My girlfriend came over with her daughter who just got back from Cuba. Her daughter was like, ‘I am so excited to sit and talk with you!’ I was like, ‘Oh please––drop the shit. I am just old and I am lucky to be alive, to be here, and just relax!’ [Laughs] It kind of shocks me because I do not think of things like that mainly because I have these towering female figures who I am awe of like Fannie Lou Hamer, Shirley Chisolm, Barbara Jordan who are just like––wow. I am just kind of a side player. Half the time I forget I am also old, so everyday I have to remind myself that I am 72!’ [Laughs] My students––I just retired not too long ago––I am always in awe of them. They said, ‘Denise, can I text you something?’ and I was like, ‘What’s text?’ [Laughs] They were like, ‘Text to your phone’ and I said, ‘I don’t think my phone has that.’ And they all started busting out laughing! They said, ‘Oh my god, we have to fix you.’”

“We share and to me that is the beauty of it. There should be those kinds of dialogues between generations. We may not be on the same technological level but we can share the beauty of our art, our music, our culture, our politics, our woman-ness with each other.”

“They made me get a mobile phone and they told me what to buy. They asked me, ‘What apps do you have on your phone?’ and I am like, ‘What is an app?’ [Laughs] They put apps on it, they send text messages, and they put music. So, they are schooling me! Your generation fascinates me. And then we would share and they would ask, ‘What songs by Beyoncé do you like?’ and I was like, ‘Who?’ They introduced me to India Arie and all this stuff but they never heard of Nina Simone and I introduced them to “Mississippi Goddam” and “Four Women”. We share and to me that is the beauty of it. There should be those kinds of dialogues between generations. We may not be on the same technological level [Laughs] but we can share the beauty of our art, our music, our culture, our politics, our woman-ness with each other. I introduced my students to Audre Lorde, who they knew nothing about, and also the Combahee River Collective but they introduced me to things going on in their lives and their world. For example, Black Lives Matter was coming up. That is a good thing. The way that I can learn from those women who were before me––whether it was my great-great grandmother who murdered her slave owner––she poisoned his ass! [Laughs]––or my aunt creeping around the house with a shotgun, I learned from those things. And I guess, some younger people can learn from me and I learn from them.”

What advice would you give to young organizers today?

DOV: “No matter how much technology you have––and I don’t care if it is a mimeograph machine or Twitter––nothing is a substitute for face-to-face actual organizing. It can be boring and grueling but sitting down and talking face-to-face is important. Another thing is––and I find it to be problematic in academia and I say academia in air quotes––is that too often young people are sucked into a world that is academic that further distances you from issues in the community. I am not anti-intellectual but the way I am talking to you now is how I talk to my classes. My dad taught me that if you cannot communicate directly to your grandmother and your grandmother cannot understand you––if you have a Ph.D. in English literature and your grandmother cannot understand what you are talking about, you’ve failed.”

“My dad taught me that if you cannot communicate directly to your grandmother and your grandmother cannot understand you––if you have a Ph.D. in English literature and your grandmother cannot understand what you are talking about, you’ve failed.”

“The epistemological, normative, deconstructing of the paradigm shift’––you know what my response to that is? What the fuck did you just say? It is seductive and it is also how you make your way in academia. You get your resume, research, and this and you learn the lingo but I call it ‘jarbage’; jargon that is garbage [Laughs]. That can get you an associate professorship but that ain’t goin’ to get you to talk to this lady having problems with social security on the block. They ‘edumacate’ you away from being able to talk to your own people. And that is dangerous. Like I said, it is very seductive and I say that to young college students in particular because academia is a game, just like everything else. You have to learn how to play and you have to learn how to speak that language but you need to be able to code switch out of it. Don’t let it seduce you to becoming not a member of the Black community anymore.”

You can follow Ms. Denise Oliver-Velez on Twitter.

You can read her work on the Daily Kos here.