Meet Jilchristina Vest: The Activist Behind The Mural Honoring The Women of the Black Panther Party

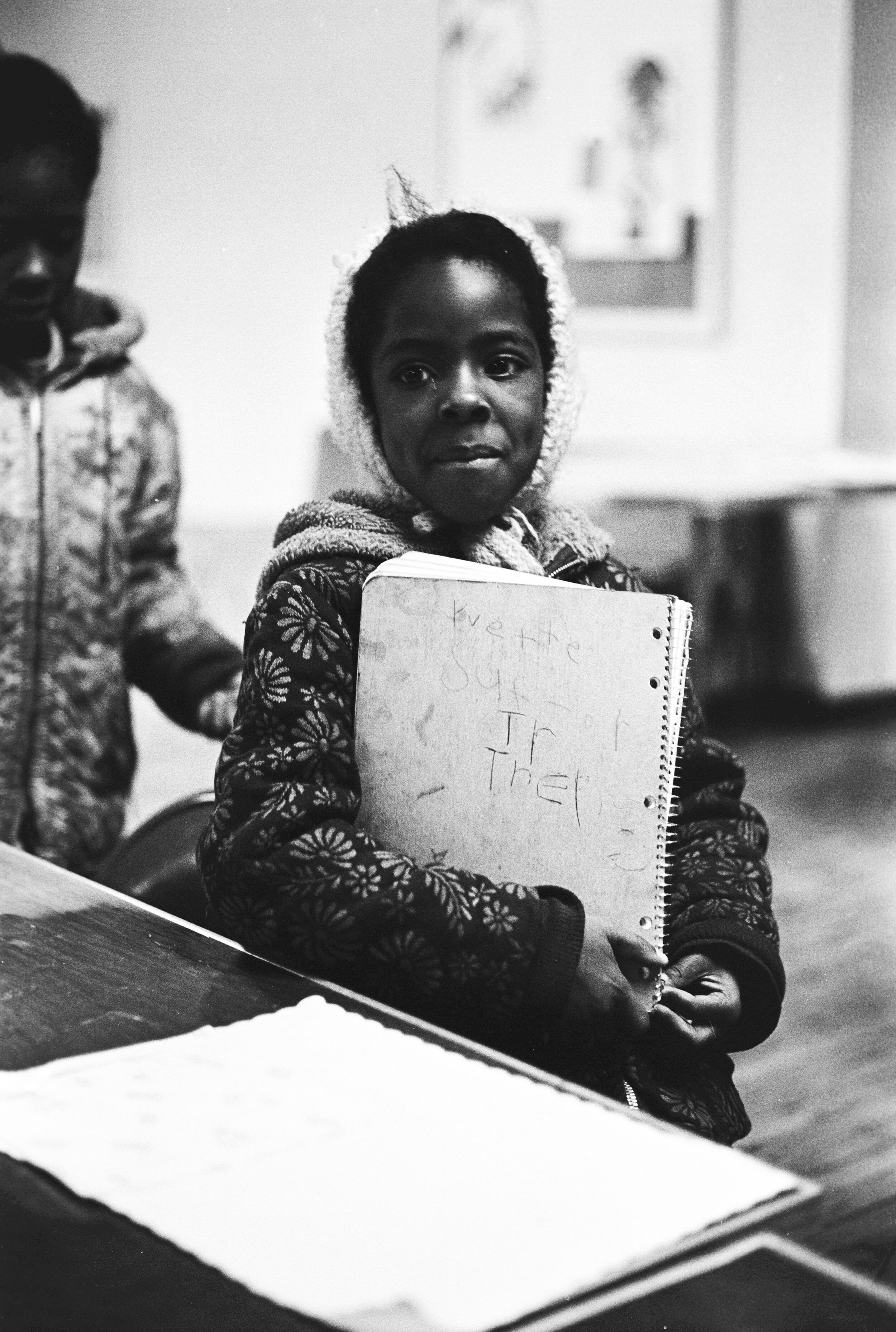

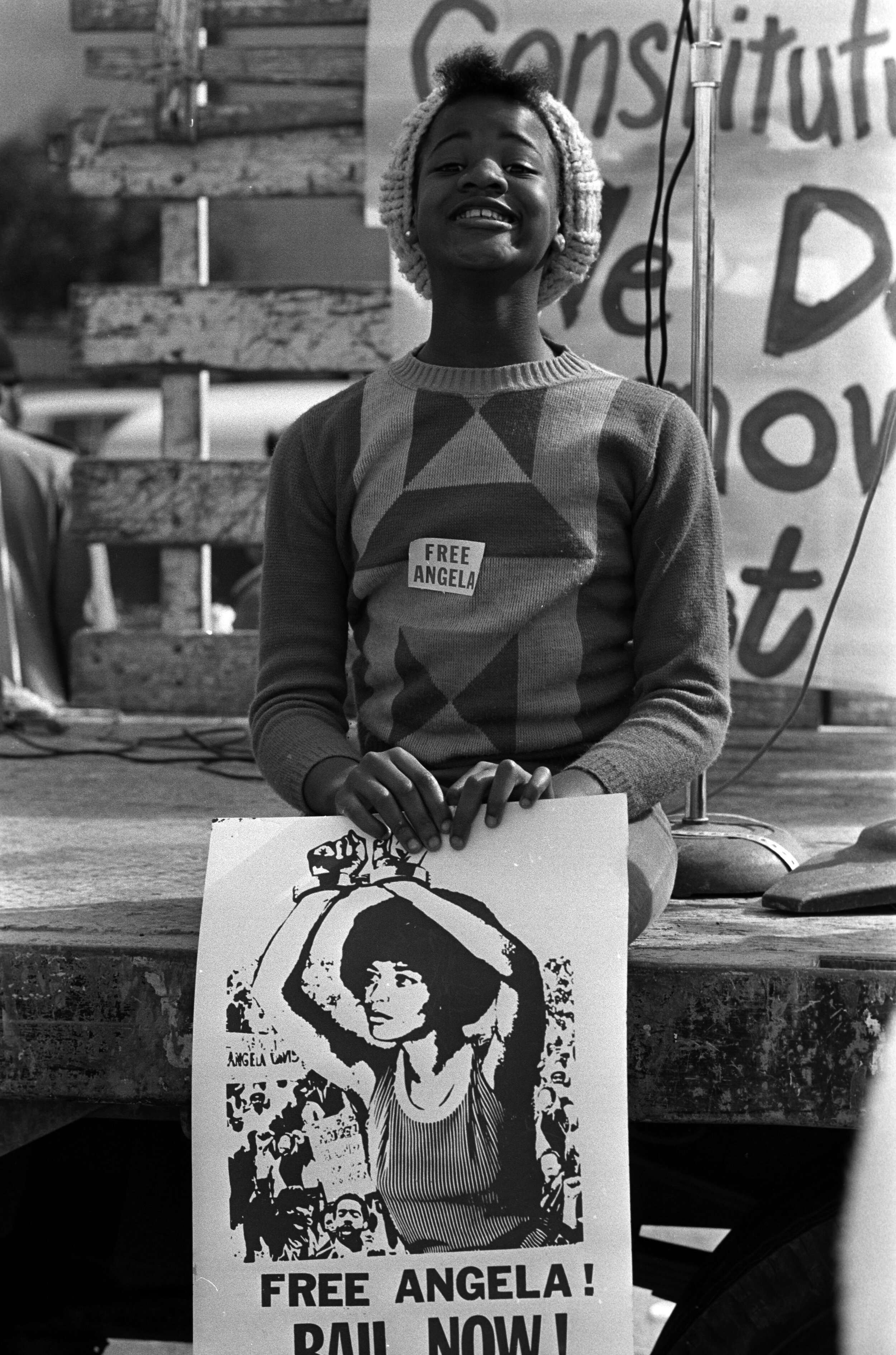

Photos courtesy of Stephen Shames and the Women of the Black Panther Party Mural Project.

By Jaimee A. Swift

Inspired by the art that emerged during the uprisings for Black lives in 2020, Jilchristina Vest is making history by organizing the first-ever public art installation honoring the women of the Black Panther Party and the #SayHerName movement.

Last year Jilchristina Vest, just like so many others, was dismayed at the state of America. With the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of U.S. governmental response to the crisis, Vest thought things couldn’t get any worse.

But it did.

In late May 2020, millions of people around the world took to the streets and demanded justice for George Floyd, a Black American man who was murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020. Floyd was arrested after a store clerk alleged he had given him a counterfeit $20 bill. What catalyzed nationwide and global protests was a video that showed Chauvin kneeling his knee on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, while Floyd was handcuffed and pinned to the ground.

While Vest was disturbed and saddened by Floyd’s death and the countless Black lives lost to anti-Black state violence, she quickly noticed there were no protests en masse for Breonna Taylor, a 26-year old Black American woman who was fatally shot while sleeping in her Louisville, Kentucky apartment on March 13, 2020, two months prior to Floyd’s murder.

Acutely aware of how often Black women and girls are overlooked in socio-political discourses, Vest wanted to change this narrative by centering the leadership of Black women who have always been the bedrock of Black radical movement building in the United States and beyond.

Inspired by the powerful art that emerged during the uprisings for Black lives last year, Vest decided she would have a mural painted on the side of her Oakland, California home in honor of women like Taylor and the women of the Black Panther Party who occupied two-thirds of the Party’s membership. The 2000 square foot mural––which is the first ever public art installation in honor of the women of the Black Panther Party and will be revealed on Valentine’s Day 2021––will feature over 250 names of unsung and unknown heroes who led, organized, and activated their communities and fought for the oppressed. According to the Women of the Black Panther Party’s website, the mural is “the most comprehensive collection of names celebrating the women in the Black Panther Party in existence.”

The mural is also dedicated to the #SayHerName movement, a campaign launched by the African American Policy Forum and the Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies (CISPS) that centers the names and lives of Black women and girls who are victims and survivors of gendered, anti-Black police violence.

I spoke with Vest about what initially brought her to Oakland, California; what the Black Panther Party and the women of the Party mean to her; why it is imperative to honor Black women’s leadership at this political juncture; and what a Black Woman Radical means to her.

Jaimee Swift (JS): I am very interested in your background. What initially brought you to Oakland, California?

Jilchristina Vest (JCV): “The Black Panther Party brought me to Oakland. I definitely feel that in my soul. I was born in Chicago in 1966. I was born the same year of the Black Panther Party. Once I came into my twenties, I wore that as a badge of honor. I always said I was a kinder Black Panther because I was born the same year the Party was born. I was born in Chicago, which was a major historical place for the Party as well. I lived there until I was 17 and moved to Arizona; lived in New York for a while; and I moved to California when I was 19. I moved here because my mother lived here but I stayed here because I saw people who looked like me for the first time. I am first generation mixed––my mother is white and my father is Black. I grew up in Chicago, which is one of the most racially segregated and racially discriminatory places I have ever been. Being from a family that was mixed, there weren't many families like that. Even though we were raised Black identified and I identify as Black, it still was a different look.”

“When I got to San Francisco, I was walking around and I saw Black women who had hair like mine and I saw families that looked like mine. That is why I decided to stay there. In 1992, I moved to Oakland and all my friends from college had moved there. I went to San Francisco State University for my undergraduate and went to the University of San Francisco for my master’s in International and Multicultural Education. In the mid-1990s, I worked for this organization called OCCUR which was founded by David E. Glover, an amazing brother who has since gone on to be with the ancestors. One of my jobs with OCCUR was to create these beautiful map-like neighborhood profiles that talked about the histories and demographics of neighborhoods all throughout Oakland. That is how I came to West Oakland and why I live here today. Because of that job, I was able to interview and learn the history of West Oakland. I also think that knowing the Black Panther Party was born in West Oakland also really solidified things. When I was in undergrad, some of my professors included Angela Davis, Donna Hubbard, Johnetta Richards, and Laura Head––all of these brilliant Black women who were fiercely political, fiercely intelligent, and unrelenting in their desire to change the world and educate the next generation about what was going on.”

“I did these neighborhood profiles and I started to learn more about West Oakland. I learned about the Seventh Street District and how hustling and bustling this neighborhood was. It was the only place in Oakland where Black people were allowed to live. So you had Black, Brown, and Asian people living here because they were not allowed to live anywhere else. It was a beautiful community in the early 1930s and 1940s. Seventh Street, which is two blocks away from me, there were all these speakeasies and there were Black doctors, Black lawyers––everyone was here during that time. When I was looking at these houses and doing these profiles, I would close my eyes and imagine what this neighborhood looked like during that time. The nefarious history––which is not surprising but still is always shocking––is that because the people here were a little too successful, in three decades they destroyed West Oakland and turned it into a ghetto. It is similar to what happened in Tulsa, Oklahoma but they didn’t bomb it. In three decades––and all using eminent domain––they bulldozed a two-mile long neighborhood; took over the houses; displaced communities into projects; and built a freeway that severed from where I am to downtown Oakland and other parts of Oakland. They ended up bulldozing other areas and built a main post office and the West Oakland Bart Station. They basically surrounded this area, which is referred to as the “Lower Bottoms”, with a freeway, a metro station, and a post office. They severed this community from everything. There are no grocery stores or gas stations over here. There was nothing. It became a ghost town, it became the Lower Bottoms, and it became a community where you didn’t go unless you knew somebody or you didn’t come back out––those were the rumors being circulated about this community. You have these Panthers coming in 1966 and they had their headquarters here. Oakland is where the first Black Panther Party Free Breakfast Program occurred at St. Augustine Church. I was able to interview people who were living in Oakland during the rise of the Black Panther Party.”

“The Black Panther Party brought me to Oakland. I definitely feel that in my soul. I was born in Chicago in 1966. I was born the same year of the Black Panther Party. Once I came into my twenties, I wore that as a badge of honor.”

“I was doing these profiles in 1995 and I said, ‘I am going to live in West Oakland. I am going to buy one of these houses. I am going to get all my friends to buy a house, we are going to make a compound, and we are going to continue the legacy of the Black Panthers. We are going to clothe our people, feed our people, and educate our people.’ I was so serious––no one took me seriously! [Laughs] I started to look for a house in 1998 while I was in graduate school. I found the house I live in now in December 1999 and it did not look like something anyone should purchase. However, I was able to buy it––which is why this mural is so important––because of my community. I had no money, I had two jobs, and I had no credit. I don’t come from a wealthy family or background. I told my community I wanted to buy this house and asked them if they could help me. I had to come up with a $40,000 down payment. I had about $400 in my bank account. I came up with the $40,000 because my community came through and lent me and gave me the money. However, the day before escrow, I was short $20,000. I had to come up with $40,000 but I only raised $20,000. I called a friend who was rooting for me and who supported me and told her that I failed with the house because I was unable to raise enough money. I was so devastated. This happened because someone had promised me they were going to help me purchase the home but backed out when they saw the house was located in ‘the hood’ and didn’t want to help anymore. They didn’t see the vision.”

“I called my friend and was crying. I told her I didn’t have enough money. She told me not to worry and told me that everything was going to be okay. I didn’t even know what that meant at the time. About ten minutes later, she called me back and told me that she talked about the house with her partner and they were both going to lend me the money. It has been 21 years and I still get chills telling this story. The next day I went to the bank with my friend and she wrote a cashier’s check for the remainder of the funds. I went on the BART train and I busted through the escrow office. It was pouring down rain that day. I was soaking wet but I got to the escrow office five minutes before noon, which was when the remainder of the money was due. And on February 14, 2000 was when the realtor handed me the keys on Valentine’s Day. It took two years to renovate the house, which was also because of my community.”

“In June 2002, I moved into the house. Over the course of me living here, the Panthers came back into the mix in a way that I didn’t realize. My house sits directly across the street from where Huey P. Newton was felled in 1989. I had no idea about that when I bought the house. It doesn’t happen anymore but there used to be a group of young Black Panthers who would march to wear Huey was murdered and march in honor of him. The connections to the Black Panthers just kept coming. I realized the headquarters of the Black Panther Party––1048 Peralta Street––was around the corner from my house. Lil’ Bobby Hutton’s grandmother’s house is five doors down the street from me. It really was meant to be my house as far as I am concerned. The owner who had the house before me was offered a lot more money than I was able to offer. I wrote him a letter telling him that he had to sell me this house because this was my house. I told him that this wasn’t about him making money––because I didn’t have any money––but that didn’t make a difference because this was my house! [Laughs] And he did sell it to me because of my letter. It is interesting because there are a lot of connections and it is continuing to happen because of the mural.”

Images of Jilchristina Vest’s house in West Oakland, California throughout the years. The women of the Black Panther Party mural will be painted on Vest’s house with a reveal of the mural on February 14, 2021. Photo courtesy of JIlchristina Vest.

JS: What has been the most rewarding aspect of the mural? Any difficulties? Do you mind sharing a little about the process of curating the mural? What have you learned about yourself and the women of the Black Panther Party during this process?

JCV: “This has been an extremely arduous process that has not been terribly enjoyable most of the time. I started off really excited with the process. It is not quite that way anymore but it is the same feeling when I bought the house. This mural was terrifying to do, it is stressful, it is scary, and it is the right thing to do. This is what I am reminding myself. The Panthers weren’t Panthers because it was easy. None of us have fought the system and fought for liberation because it was easy. It has nothing to do with it. I have to really remind myself and know that I am doing something right when it is difficult and when people are pushing against you and when haters come out of the walls. You start to realize you are really ruffling some feathers. So much of this angst about the mural has come from Black men. And I am not going to back down to anybody. I take up a lot of space as a woman. A lot of times I’ve apologized for it. However, the older I get I realize that I am unapologetic about it––I have a right to take up this space. I feel like as a Black woman, and being in so many of the situations I have been in, I have been grasping at the root from a very young age and trying to change things. However, I have noticed throughout my life that when men do certain things it is deemed acceptable and women do certain things there is a different response.”

“The Panthers weren’t Panthers because it was easy. None of us have fought the system and fought for liberation because it was easy.”

“This started most clearly at San Francisco State University in Black Studies and in the Black Student Union and how Black women were rendered invisible. Our voices, our thoughts, our theories, and our analysis were rendered invisible. We had to fight constantly to demand a place at the table. I have been a fighter for justice since a young age. However, later on when I became more active, I had to speak louder and louder to speak over the misogynoir. Now, I go back and forth and think about how I don’t want to bulldoze things but when I see people not doing the right thing, I have to check people then and there––I cannot stay silent. Nobody else is saying anything and I don’t care if you are 23 or 53, somebody has to tell you and somebody has to hold you accountable. There is joy and I am excited. It has been stressful but there is joy.”

“I’ve learned throughout this process that not everyone has the same work ethic as I do. I have a fierce work ethic and when I say I am going to do something, I do it and I am going to do it with excellence. I also learned that I am not patient. [Laughs] I need to be patient and it is very hard to be patient. I want things done quickly and I want them overnight. What I am trying to coordinate with my brain and in my spirit is that I need to woosah. I need to flow, let things unfold, I need to pause, and I need to ask more questions. I need to look at my surroundings before I jump and go one way or another.”

Photos of the mural in progress on the side of Jilchristina Vest’s West Oakland home. Rachel Wolfe-Goldsmith is the muralist, lead designer, and the artistic team director for the Women of the Black Panther Party Mural Project. Photos courtesy of Jilchristina Vest.

JS: This mural is the first-ever public art installation honoring the women of the Black Panther Party. How do you think this mural will impact how current and future generations interrogate the lives, activism, leadership, and legacies of the women of the BPP and even how we think about Black women's leadership in general? Why was and is it so important to you to honor their work, especially at this political juncture?

JCV: “That is going to be up to us, isn’t it? I am going to do whatever I possibly can to start this conversation. What birthed the mural––and this is emotional for me––was my level of despondency in what is happening in the world and in America. When May of last year was happening and I saw everybody take to the streets for a Black man, and nobody took to the streets for Breonna Taylor––and she had been killed two months before and she was asleep! Nobody took to the streets for her. How many times are we going to be brutally murdered by the police, and they are going to film it, and plaster it all over the news? However, what was breaking my heart was not white people. I am not shocked at all by white people. They are predictable, they are consistent, and they are fighting for what they rightfully think is theirs. That is not rocket science. They believe that because they are white that they think they should be in control and they are going to fight for it and they have been doing that consistently and predictably for generations. Nothing they do shocks me. But I keep getting shocked by us and how we engage one another.”

“With the onslaught of COVID-19, it was already a heavy situation. The mural was birthed because I was trying to combat the depression, the despondency, and the dark place my spirit was going. My spirit was going to a place where I was thinking that we will never get out of this shit-show and that this is how it is always going to be for us. And we do have our valleys and our lows. What I have become better with, especially due to Buddhism and meditation, is to acknowledge what I was feeling is a real emotion and it was allowed to take up space. I stayed in the sadness for a while and allowed it to unpack itself. I then realized I couldn’t stay there and then it became about Black joy. It didn’t happen overnight but it got there. I realized that I did not have enough joy in life. I am seeing all this Black death and Black tears. I started to see the aftermaths of the protest that produced all this beautiful art. I was seeing all this rage and how this rage turned into a mural in downtown Oakland. I started to see the balance––this is the balance.”

“So much of this angst about the mural has come from Black men. And I am not going to back down to anybody. I take up a lot of space as a woman. A lot of times I’ve apologized for it. However, the older I get I realize that I am unapologetic about it–I have a right to take up this space.”

“One day, I had to drop my car off and instead of getting a loaner car, I decided to walk back to my house. I was about three miles from my house. I took a walk down Broadway and just photographed all these murals. I said to myself, ‘I want to see them before they take them away. I know they are going to take them away because this is a reminder to them what they are doing to us.’ I took all these photos of the murals and quotes. I realized those murals were going to be covered up and disappear one day. This was around the time where all the monuments were coming down across the world. I sent an email to folks that spoke to the importance of us honoring those who fought and died for our liberation. I was in my den one day and just stopped and thought, ‘I am putting a mural on my house. That is what I am going to do.’ The original mural was supposed to be very small and on the main wall of the house. It would have cost a couple of thousands of dollars. No big deal! [Laughs] I miss the days when it was going to be a small project!”

“So, that is how the mural was born. It was around May 31st or June 1st of last year. I went and took pictures and put it on Instagram and asked, “What muralist is out there who wants to put a mural on my house? It will be permanent and no one can ever take it down. It will be honoring Black women and the #SayHerName movement.’ After that, I went out of town on a retreat and forgot all about it. I come back home and my neighbor says to me, ‘We’ve already raised $2,000. Did you hire a muralist?’ And I was like, ‘Oh, shit. This just got real.’ I checked on my Instagram and I had all these responses. It was really great.’

“The first brother who I found to do the mural was a neighbor. He was replaced. And the second brother who I found to do the mural, he was replaced also. And now, I have an all-women’s team.”

Photos courtesy of Stephen Shames and the Women of the Black Panther Party Mural Project.

JS: How have the women of the Black Panther Party received the creation of the mural?

JCV: “It has been fantastic. It has been very exciting. When it was first happening, I was getting all these phone calls from Panther women from across the country. I was having these amazing conversations with these elder sisters and they all mentioned to me they had never really been recognized and that no one really asked them what they did. They told me that no one has really honored them for everything they did. When I decided to do the mural, it started off as a mural in honor of the #SayHerName movement. I found all these connections with women that I felt I had a kindred spirit with such as Sandra Bland and Kimberlé Crenshaw. The #SayHerName movement was very meaningful to me and that is where it started. But then I started to think about all the Black women from Oakland and from the Black Panther Party who never really were honored and whose names are not said or spoken of outside of Angela, Kathleen, and Assata. That is not what the Panthers were about. I texted Ericka Huggins and told her this is what I was doing and I asked her for her blessing for the mural. She told me I made her day and that was the best text she ever got.”

“When you asked me about how the mural will impact future generations, I did not answer it fully. When I first gave my response, I meant that for myself there is only so much that I can do. The ownership of the mural ends at the property line. Once the mural is up, it is not mine. It belongs to everybody. Just like we all have responsibility for our liberation, it is everybody’s job to educate ourselves, to free our communities, and to feed our communities. Something I have been doing from the very beginning with the mural is to get everyone involved with it as much as possible. The main impetus for doing the mural is because I live in a historically Black community and I have an elementary school at the end of my block on Peralta––the same street where the Black Panther Party headquarters were. I’ve lived here for twenty years and the kids walk past my house everyday. I want for Black girls and Black people––but mainly Black girls and Black women––to see this mural. Being Black juxtaposed to white supremacy is very burdensome. It can bend your shoulders and your back. You keep going but it is heavy. It’s really heavy. I want this mural, which is all about joy and celebration, to not be about what they have done to us but about what we have done for ourselves. This is why we need to celebrate, educate, and remind the generations under us about what we can do for ourselves. Anybody who walks up to this mural, I want their shoulders to go back, I want their necks to get longer as they look up, and see themselves reflected and see the power in these Black women and say, ‘I want to learn about the women of the Black Panther Party.’ I want them to walk up to the mural and read the names of the women of the Black Panther Party and be able to see all this information they have never seen before. More importantly, I want them to see themselves. I want them to see their aunt or grandmother or see their neighbor. That is what I am trying to do––I am trying to create a space where Black women’s names are said and are embedded into history and where images of Black women are forty feet tall and are towering over and are protecting a community. I want that to happen literally and figuratively because we need to straighten our backs.”

“...I was getting all these phone calls from Panther women from across the country. I was having these amazing conversations with these elder sisters and they all mentioned to me they had never really been recognized and that no one really asked them what they did. They told me that no one has really honored them for everything they did.”

“Ericka is such a huge part of this mural because she told me that when she would lecture around the world, she would list the names of women of the Black Panther Party and try to get people to remember that 70 percent of the Black Panther Party were women at the height of their membership. A brother told me that in the San Francisco chapter, there were three women to one man and that they knew the women did everything. I did not know it was women who were managing the 60 plus survival programs across the country. What the women of the Black Panther Party did was, they saw a need and they dealt with it. They saw a child with no shoes? They decided to do a free shoe program. They saw a child with no coat? They created a free coat program. Ericka told me that there was nothing special the Panthers did. There was nothing they did that had this extra special and magic secret formula that was only available from 1966 to 1982. Everything they did could be replicated today if we wanted to.”

Photos courtesy of Stephen Shames and the Women of the Black Panther Party Mural Project.

“I want for Black girls and Black people–but mainly Black girls and Black women–to see this mural. Being Black juxtaposed to white supremacy is very burdensome. It can bend your shoulders and your back. You keep going but it is heavy. It’s really heavy. I want this mural, which is all about joy and celebration, to not be about what they have done to us but about what we have done for ourselves.”

JS: What does a Black Woman Radical mean to you?

JCV: “A Black Woman Radical to me is someone who refuses to stay in the place that she keeps being put in. It is a Black woman who refuses to be boxed in or silent. A Black Woman Radical is someone who has a lot of people pissed at her most of the time. [Laughs] A Black Woman Radical is relentless, unstoppable, and is innovative in that I am going to keep trying to figure out everyday how I can participate in my freedom and my people’s freedom. Everyday that I am alive, I am going to figure out something I can do, say, and write that contributes to the liberation of Black people. A Black Woman Radical needs to be void of ego and arrogance. A Black Woman Radical has to be armored in a way that I have wished so many times that I didn’t have to be. It is wanting to be soft, vulnerable, and sensitive, and a soft-celled human being but not being allowed to be that because there are too many daggers.”

“A Black Woman Radical and fighting for liberation does not have to be a big gesture of a 2,000 square foot mural. I often get involved in things I shouldn’t get involved in. I have found myself often seeing an injustice in the middle of the street and standing in between the injustice and saying no. Someone said to me, ‘One of these days Jil, you are going to get shot.’ And my response was, ‘Well, I don’t know what you want me to do with that information because I could get shot for no reason, so I might as well get shot for a reason if it is going to happen.’ A Black Woman Radical is more interested in their people’s freedom than they are of their own. I am more interested in the safety and freedom of Black girls than I am my own. Their safety is more important than mine. I will always be that person.”

For more information about the Women of the Black Panther Party Mural, please visit the website here.

You can follow the Women of the Black Panther Party on Instagram here.