The Triumph of Black Lesbian Feminist Resistance: Honoring Radical Poet and Activist Cheryl Clarke

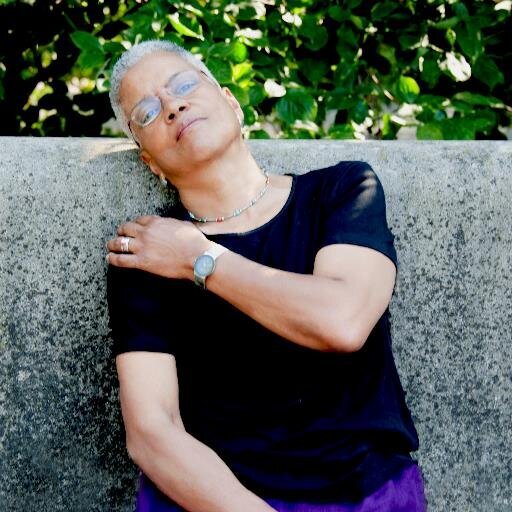

Award-winning poet, activist, essayist, and educator, Dr. Cheryl Clarke. Photo courtesy of Dr. Cheryl Clarke. Photo Credit: Nivea Castro.

By Jaimee A. Swift

As a pioneering poet, activist, essayist, and educator, Cheryl Clarke has and continues to center and uplift radical Black lesbian feminist literature and organizing. We honor her.

“Visions of Black liberation which exclude lesbians and gay men bore and repel me, for as a Black lesbian I am obligated and dedicated to destroying heterosexual supremacy by ‘suggesting, promoting and advocating’ the rights of gay men and lesbians wherever we are. And we are everywhere.”

To say that Cheryl Clarke is brilliant is an understatement. A poet, writer, essayist, and educator, Clarke has not only spotlighted pervasive injustices committed against the Black community but she has been (and continues to be) pivotal in uplifting and centering radical Black lesbian feminist politics, perspectives, and praxes. A pioneer in so many aspects, Clarke has certainly laid a powerful blueprint for present and future Black lesbian and queer feminist theorizing, organizing, scholarship, and leadership.

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1947, at a young age Clarke became intrigued with writing; in fact, she has been writing since she was five-years old. Growing up during the height of the Civil Rights Movement and having faced the perils of segregation first-hand, Clarke became politicized at a young age. At 16, Clarke, along with her parents, attended the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Before the march, Clarke met and had a quick encounter with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Attending Howard University for undergraduate and receiving her Bachelor’s in English Literature in 1969, Clarke attended Rutgers University for graduate school and received a master’s degree in 1974, a master’s in social work in 1980, and her Ph.D. in 2000. A dynamic educator and administrator, Clarke taught at Rutgers for 41 years and retired as the Livingstone Dean of Students in July 2013. While she was working at Rutgers, she was instrumental in ensuring LGBTQ+ rights and representation on campus. She founded the Office of Diverse Community Affairs and Lesbian-Gay Concerns, which is now the Office of Social Justice Education and LGBT Communities. Because of her dedication and service to LGBTQ+ students at Rutgers and LGBTQ+ communities broadly, she received the David Kessler Award.

Known for her unabashed critique of homophobia, sexism, racism, and more in and out of the Black community, Clarke has written many influential essays as it relates to the Black queer community such as “Lesbianism: an act of resistance”, which was published in the book, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color (1982) edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa and “The Failure to Transform: Homophobia in the Black Community,” published in Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, edited by Barbara Smith (1983). She was also an editor of Conditions, a lesbian literary magazine and serves on the board of directors of Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal. In 2018, Clarke co-edited Dump Trump: Legacies of Resistance, a special issue of Sinister Wisdom. She has published five collections of poetry including Narratives: Poems in the Tradition of Black Women (1983), Living as a Lesbian (1986), Humid Pitch (1989), Experimental Love (1993), which was nominated for a 1994 Lambda Award and By My Precise Haircut (2016), which won a Hilary Tham Capital Competition. She also wrote “After Mecca”: Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement (2005), and a volume of her poetry, The Days of Good Looks: Prose and Poetry of Cheryl Clarke, 1980–2005.

Considering herself a “scholar of Audre Lorde”, Clarke has written extensively about the profound legacy of Lorde’s life and literature. She wrote the introduction to G.R.I.T.S: An Anthology of Writing by Southern Black Lesbians (2013) and her article, “By Its Absence: Literature and Social Justice Consciousness” was published in The Handbook of Social Justice (2014). In 2008, Clarke co-edited with Steven G. Fullwood, To Be Left with the Body, a literary publication of the AIDS Project Los Angeles for men of color who have sex with men. Her poems and essays have appeared in countless anthologies and journals such as The Black Scholar, The Kenyon Review, Belles Lettres, The World in Us: An Anthology of Lesbian and Gay Poetry, and Persistent Desire: A Femme-Butch Reader (1992).

Clarke is the co-owner, along with her partner of 24 years, Barbara J. Balliet, of Blenheim Hill Books in Hobart, New York. She and Balliet are involved in the organization of the annual Hobart Festival of Women Writers.

Black Women Radicals spoke with Dr. Clarke about what led her into her work; why poetry is a tool of resistance; her experiences at Howard University; what radicalism means to her; and more.

Jaimee Swift (JS): You are a pioneer in so many facets. What was the catalyst or moment that led you into your activism or sparked your activism?

Cheryl Clarke (CC): “I think I was very influenced by the Black Arts Movement and the Black Power Movement. That changed my consciousness about myself and Black people. When I came out as a lesbian, I felt I was definitely influenced by the Black Arts Movement and it changed my consciousness as a Black person. Lesbianism––lesbian feminism––changed my consciousness as a woman. So I saw myself as a Black lesbian who was doing something different. I never wanted to live a traditional woman’s life. And lesbianism gave me the opportunity to do something different with my life as a woman. I was already a practicing poet, so that already kind of puts you out in left field, too; well, not left field but you know, this is a prose privileging culture. Being a poet, being a lesbian, and Black, gave me a wonderful opportunity to do something different and to have an influence on others. I guess all of that led to what you are calling activism. The article, “Lesbianism: an act of resistance” I think that was right out of the Black Arts playbook because of the way it sort of called lesbians to arms––I am using that metaphorically. It was intended to sound angry and insistent. And people kind of liked that. I mean that is how it initially happened.”

“Lesbianism–lesbian feminism–changed my consciousness as a woman. So I saw myself as a Black lesbian who was doing something different. I never wanted to live a traditional woman’s life. Lesbianism gave me the opportunity to do something different with my life as a woman.”

“I spent a lot of time in New York City and I got involved with writing. This Bridge Called My Back opened me up to a lot of other contacts and communities. I got involved with Conditions magazine, which was really a journal and I was an editor of it. There actually were seven of us at all times but I was there for nine years. I edited for nine years. That was an excellent experience for me because it showed me how to create books because I self-published my first book of poems. And I still self-publish from time to time. So that was an excellent experience, Conditions magazine. Did you ever see Home Girls? Well, Conditions Five: The Black Women’s Issue came out in 1979 and actually was the basis of Home Girls, which came out in 1983 or 1984. In fact, this Bridge Called My Back was out of the Conditions Five playbook because Cherrie and Gloria did [that] book [and] that book is still alive and is still influencing people. “Conditions Five and This Bridge [Called My Back] caused a sea change in terms of women of color publishing. So it was very exciting to be part of that. And I guess I am still part of it. You know I work with Julie Enzer and others on Sinister Wisdom, which is like over 40 years and I think is the oldest extant lesbian journal. I am still involved in lesbian publishing. And in fact, we are going to try to do a special Sinister Wisdom edition on Africa.”

Poet, activist, essayist, and educator, Dr. Cheryl Clarke.

JS: When you think about all the work you have done in impacting Black lesbian feminist politics, how does it feel to see the new generation of Black queer feminist movements today?

CC: “I am happy to see it! This is the thing: feminism helped women so much because if you take it seriously you are going to take that leadership into other areas. Like okay, take Barbara Smith. She founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. But when she left Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, she went to Albany, New York and was voted and won an election as a councilperson and she was on that council for eight years representing a working-class, poor, Black and Latino community. That is where her feminism led her. Just like those women who founded Black Lives Matter, that is where their feminism took them. I feel happy about the leadership of Black queer women.”

“This is the thing: feminism helped women so much because if you take it seriously you are going to take that leadership into other areas.”

JS: Were you a member of the Combahee River Collective?

CC: “No, I wasn’t. Everyone thinks I was but I wasn’t. I knew Barbara during that time; well many of us knew Barbara during that time [Laughs]. One of the things Barbara did was–which she doesn’t talk about but she should (but others have): she sponsored between ‘77 and ‘80 four Black feminist retreats. About 12 or 13 of us attended them. And actually, we were from all over the country. People came from California, Chicago, New York, andConnecticut. But that was what I was a part of. That was after Combahee.”

JS: How was that experience for you?

CC: You mean the Black feminist retreats?

JS: Yes.

CC: “Oh, it was great! That was a lovely experience actually because we would be together for a weekend. We had the consciousness-raising model where everyone would go around and say something. You could almost talk as long as you wanted to and people couldn’t cut you off or they couldn’t disagree with you, that was the practice [Laughs]. We communed like that from ‘77 to ‘80. Audre Lorde was part of it for a while. I think there was too much of an age difference––I think she felt that too much. But she was part of it. Akasha Gloria Hull was a part of it. We sort of had a reunion at UMass-Amherst when they did a conference on June Jordan. You know, the Combahee River Collective and the Black feminist retreat people sort of had a reunion. It is almost so long ago that I don’t even remember but I remember feeling very excited and very sexy because all those lesbians were together, you know! [Laughs] Anyway, that was very helpful because we could see that we weren’t the only ones–that we weren’t the only Black feminists. There were others. And that grew. They grew even more with the publications. It was a great thing to commit my life to because I didn’t have anything else worth doing.” [Laughs]

JS: Your poetry has always challenged oppressive structures and norms. How has poetry been a tool of resistance for you?

CC: “Well, I keep writing it. I keep using it to explore the politics of the time. I write quite a bit about the racist treatment of Black people. I write a lot about police brutality and about Black history. I try to still approach sexuality and I guess I still kind of see lesbian sexuality as renegade sexuality. I hate to make it sound so instrumental but poetry is a tool for me. I think we always have to resist and challenge heterosexuality because it is always raising its ugly head somewhere. You know what I mean––I don’t mean it like that. Well, I was looking at something on BET and it was something silly and it was something heterosexual. You go to Howard, don’t you? You see it there, don’t you? There must be a Black queer student organization there, right?”

JS: Yes, there is!

CC: “Well, I am glad they are still going. I came [to Howard] during the 90’s because I came to talk to a class. Do you know Eleanor Traylor?

JS: No, I don’t actually.

CC: Well, she was a good friend of Toni Morrison’s. And she taught at Howard in the English department. Actually, she was in the Theater Department at the School of Fine Arts at Howard. But she was a brilliant woman and I went to talk to her class. This was while I was working on my doctorate. And the lesbian-gay organization––because we didn’t use the term ‘queer’ back then––they asked me to speak to their organization. Well, I said, ‘God damn, this is something! Howard University has a gay organization!’ I thought it was very good. They were asking me questions about literature. I was telling them about reading between the lines in slave narratives and how you can suss out the homosexuality. Because whenever in the slave narrative they say or what Frederick Douglass said something to the effect of, ‘They committed such abominations on my person that I can’t discuss’, well, you know that was sex. You know that was rape. We are used to women saying that in the slave narrative but men can’t talk about it.”

JS: When you were at Howard, there was no LGBT organization? How did you navigate that?

CC: “No! No! No! In fact it is very interesting––the woman who was the editor of the newspaper, The Hilltop––does it still come out at Howard?

JS: Yes, it does!

CC: [Laughs] The Hilltop….the newspaper was very radicalized and got radicalized very quickly. The woman who was the editor of it––what was her name? I can’t think of her name now. She was very, very smart and very, very political. She just wasn’t sitting up and talking rhetoric. But her roommate was a woman who was quite gorgeous. They were together during the time I was at Howard. I mean, there was no LGBT anything [at Howard]. And nobody was out. We find out later that people were gay or lesbian. And then you had eccentrics like Owen Dodson who was definitely gay and nobody better say anything because he was an esteemed dramatist. So you know there were eccentric people who were gay or lesbian. Actually one of the women, a white professor in philosophy, I think her name was Lynda Blumenthal. Well, she refused––she was very political––to sign the loyalty oath. You know they make you sign a loyalty oath when you work for the government. She refused to sign it because she didn’t feel the need to sign a loyalty oath to the United States to teach. And she didn’t want to sign the loyalty oath because she mostly disagreed with everything the United States stood for, especially the war in Vietnam.”

JS: The students have made a lot of leeway in terms of LGBTQ+ rights and representation on campus.

CC: “That is good. People don’t have to act like it is their first time hearing about queer people, you know? But I mean, are you working on your doctorate?

JS: Yes, I am.

CC: “Well, how much longer do you have to go? Because you never know with that.”

JS: [Laughs] Hopefully by next year I will be out of there!

CC: “How long have you been there?”

JS: “I did my Master’s at Howard too, so I have been there since 2013 so for six years. I did my undergrad at Temple University.”

CC: “How did you like that?”

JS: I liked it. It taught me grit. I liked being in North Philly surrounded by Black folks. I thought I was going to be surrounded by Black folks in D.C., but I came in during heightened gentrification and it went from Chocolate City but a caramel macchiato from Starbucks. [Laughs]

CC: Yes! [Laughs]. So true!”

JS: When you think of your legacy as a Black lesbian feminist pioneer, what are you most proud of?

CC: “I guess I am proud of the writing that I have done and the work I continue to do. It is hard for anyone to talk about legacy because you have to face your mortality. That is what makes me proud of my life. [My work] and its influence on other people, younger generations. You are right, it is a platform for others to build, do their work, to build their lives upon and to be out there––to be able to be out there and to be out.”

“I keep using it to explore the politics of the time. I write quite a bit about the racist treatment of Black people. I write a lot about police brutality and about Black history. I try to still approach sexuality and I guess I still kind of see lesbian sexuality as renegade sexuality.”

JS: Do you consider yourself a radical and if so, what does a Black Woman Radical mean to you?

CC: “Yes, I hope I’m a radical. I knew you were going to ask that question! [Both laugh] I hope I am a radical. Sometimes, I am radical. You know, one can’t be all radical. You know, I have this liberal part of myself. However, look around the world––capitalism is still as deadly. Look at the White House. Look at it! All this shit comes down to money. All the shit in the Ukraine, all that going around that Rudy Giuliani did. So radical means to me is to get far away as I can get from the corrupt nonsense that our government engages us in. I take what Ella Baker said about ‘radical’ and she said that you are digging up the roots of something and changing it. I think it takes us all our lives to dig down to that root and change it. That is what radical means to me. When I think of Blackness, I think of it as an ever-replenishing resource. That is Blackness. You think about Black culture and I mostly think of Afro-American culture. You see I say Afro-American but not African-American but in this case, I will say African-American. I am also talking about the Diaspora as well as the continent.”

“When I think of Blackness, I think of it as an ever-replenishing resource. That is Blackness.”

“You know you spend all of your life learning about Blackness. You spend all your life learning and unlearning womanhood. You spend all your life––at least I have––[Laughs] trying to define and redefine lesbian and not in a lesbian separatist manner. Though that had its place just like Black nationalism had its place in Blackness many years ago during the Black Arts Movement and the Black Power Movement. Black people had to learn about themselves and they had to change themselves. Same thing with women. We had to learn about ourselves. So, I see the same process for lesbianism as well. You spend your life trying to know about it––well, I do!” [Laughs]

For more information about Cheryl Clarke, please visit here.