“This is Not a Small Voice”: Exploring the Transformative Poetry of Sonia Sanchez

By Karla Mendez

Writer Karla Mendez reflects on the power of Sonia Sanchez, whose pioneering work has changed the way we view poetry.

Sonia Sanchez: A Leading Figure in Black Culture and Literature

“Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery. The Souls of Black Folk, by W.E.B. Du Bois. And Their Eyes Were Watching God, by Zora Neale Hurston. You cannot teach Black literature without them. And of course, then you have Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Amiri Baraka.” These are the works and people Sonia Sanchez references when discussing literary works that are paramount to Black literature and history. Although speaking of others’ work, the same can be said about Sanchez and her significant contributions to Black literature and the Black Arts Movement.

Sanchez has published over a dozen books of poetry, several plays, and children’s books. She has received countless honors for her literary work, as well as recognition for her participation in the Civil Rights Movement. Sanchez has been incredibly prolific throughout her life and career, but we have to start at the beginning to understand her journey.

Poetry As Healing

A black-and-white image of Sonia Sanchez (right) signing a book. 1972. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Sonia Sanchez, or Wilsonia Benita Driver (as she was named by her parents), was born on September 9th, 1934, in Birmingham, Alabama. Sanchez’s mother passed away when she was a year old. Her grandmother went to Sanchez’s father, who was a high school teacher and musician, and told him she would raise Sanchez and her older sister, Patricia. Her close relationship with her grandmother inspired her love of poetry, language, and speech. She found herself captivated by the way her grandmother spoke, as her speech had a distinct rhythm about it. Sanchez would try to reproduce her grandmother’s rhythmic tone and dialect in her poetry.

When Sanchez was six, the special bond she and her grandmother shared was unfortunately cut short when her grandmother passed away. The tragic and unexpected loss would leave a lasting effect on Sanchez. Soon after the passing of her closest confidant, Sanchez developed a stutter that lasted until her teenage years. Discussing her speech impediment, Sanchez referred to it as a form of protection her grandmother bestowed upon her before her passing. As a child who kept to herself and was a voracious reader, Sanchez noted that an affliction like a stutter kept other kids from bothering her. Her stutter also played an essential role in her poetry, as she spent more time reading and paying attention to the rhythms of language.

Her grandmother was not the only adult in her life that influenced and nurtured her love of reading. One of her aunties (as Sanchez called them) taught her to read at a young age, which motivated her to try her hand at writing, or as she described them as “little ditties”. Sanchez wrote her first poem at five. However, it was not until she started living in New York City that she started taking writing seriously and saw a future for herself as a writer. Sanchez continued to work on her writing while completing her undergraduate degree in political science, which she received from Hunter College in 1955. Sanchez’s training continued with post-graduate work at New York University, studying poetry under the guidance of poet-critic Louise Bogan, who would encourage her to pursue a writing career.

Developing a New Form of Poetry

Bogan would take Sanchez and her colleagues to see poets read their work, and during these excursions, she would remind students that they have to practice reading their work aloud because, as Sanchez later said, the poem is the “dance of the page”. In an interview with the Boston Review, Sanchez stated:

“When you give it out to an audience, it has got to be there, pulling up, getting ready to soar, dance, spread itself, do the magic that needs to be done, to capture them, to make them enter your arena, and they don’t get released until you are at the end of that poem, then you release them. That’s the power that you and that poem will have over an audience. You’ve got to understand that there’s music in those lines and in those words. There’s magic in them. But there’s also authority in there. There’s also a responsibility—that is a part of what I teach, the responsibility that you have when you give these words out in an auditorium, in the classroom, to the universe.”

Sanchez describes poems as having music and magic in them, which is evident in her poetry. She blends musical genres like blues, jazz, and hip pop and is one of the leading poets to use African-American Vernacular English in her poetry. She is known for possessing a sonic range and presenting a magnetic performance, likely due to her grandmother’s influence and as an homage to her.

While a graduate student at New York University, Sanchez participated in a writers’ workshop in Greenwich Village, which saw various talented and prominent poets such as Amiri Baraka (formerly known as Leroi Jones), Haki Mahubuti, and Larry Neal. It was from this workshop that the Broadside Quartet was born. Along with Nikki Giovanni, Haki Mahubuti, and Etheridge Knight, the group wrote and performed radical poetry through which they shared their thoughts on the world around them and their station in life. Although Baraka is widely credited as the founder of the Black Arts Movement, with his establishment of Black Arts Repertory Theatre School in Harlem, New York in 1965, the Broadside Quartet can be seen as a foundation of the Black Arts Movement, of which Sanchez would become a leading figure.

The Black Arts Movement

During the early 1960s, Sanchez supported the idea of integration and was involved with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). However, she would later become a part of the Black Power Movement. After meeting Malcolm X through her work with CORE and listening to him speak, Sanchez shifted her opinion and agreed with his belief that integration was a myth. When she joined the Black Power Movement, she increased her referencing of African culture and heritage and the liberation of Black people worldwide. Sanchez also cited Black radical activist, playwright, Pan-Africanist, and author Shirley Graham DuBois as her mentor while she was teaching at Amherst College, and credited Graham DuBois for “…[introducing] me to international Blackness, and through that I came to be in dialogue with the work of people like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o and Chinua Achebe.”

Culturally and politically related to the Black Power Movement, the Black Arts Movement emphasized self-determination for Black people; a separate cultural existence for Black people on their terms; and the beauty and virtue of being Black. The work created by the Black Arts Movement aimed to uplift the voices of Black Americans, or as Sanchez stated, “put the African and African-American back on the world stage. Our enslavement had taken us off the world stage.”

The group was militant in nature and followed the words of Malcolm X, whose goal was the liberation of Black people. Their work energized readers to go out into the streets and protest the treatment of Black people in the United States, on the continent of Africa, and the African Diaspora. For Sanchez, she uses her poetry to keep in contact with her ancestors and to spread the truth to people. Sanchez would later join the Nation of Islam in 1972 but left in 1975 because of their often-disparaging views on women’s rights.

Breaking the Status Quo

Sonia Sanchez reading at Split this Rock in 2018 in Washington, D.C. Photo Credit: Slowking. GNU Free Documentation License.

Sanchez’s first collection of poetry, Homecoming, published in 1969 while still with the Black Arts Movement, addressed the racial oppression that the movement and Sanchez protested against through their work. With the publication of her second book, We a BaddDDD People, published in 1970, Sanchez established her status in Black literature and shared with readers the Black struggle for liberation from racial and economic oppression. Her poetry uses unconventional spelling, hyphenated lines, and abbreviations, deconstructing what is typically seen as a poem, and almost daring readers to reexamine the way language is used.

Around the same time her first two books were challenging the status quo of poetry, Sanchez applied her unique voice to her first plays, Sister Son/ ji and The Bronx Is Next. Like her poetry, her plays explore the Black Power Movement, sexism, and oppression. Ever the prolific writer, Sanchez has also published children’s books, such as A Sound Investment, published in 1980, and The Adventures of Fathead, Smallhead, and Squarehead, published in 1973.

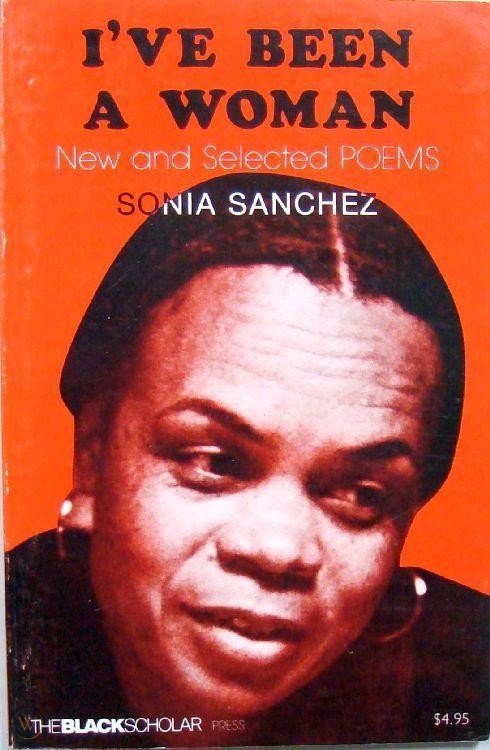

Since the 1970s, Sanchez has continued to share her activism through her work and published numerous collections of poetry (I’ve Been a Woman: New and Selected Poems and Homegirls and Handgrenades), children’s books (It’s a New Day), and written many plays (Black Cats and Uneasy Landings and I’m Black When I’m Singing, I’m Blue When I Ain’t). She has continued to produce an abundance of work that has earned her honors, such as the Frost Medal, the Lucretia Mott Award, the Peace and Freedom Award from the Women International League for Peace and Freedom, and a National Endowment for the Arts award.

The Development of Black Studies

A feature on Sanchez would not be complete without acknowledging her work in developing the discipline of Black Studies. While teaching at San Francisco State University in 1967, she introduced a Black Studies course, which was unheard of and became the first course of its kind offered at a predominantly white collegiate institution. In 1969, while teaching at the University of Pittsburgh, Sanchez presented a lecture titled “The Black Women,” the first devoted solely to studying literary works by African-American women. Through her teaching, Sanchez continued to promote freedom and justice for African-Americans and challenge the biases she saw within academic establishments.

Sanchez continued to teach, holding positions at City College of New York, Amherst College, Spelman College, and Temple University, where she remained until her retirement in 1999. Even though she is retired, she has not slowed down her writing, and inspires poets and writers alike, such as Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Reginald Dwayne Betts, Krista Franklin, and Amanda Gorman.

This Is Not A Small Voice: Reveling in the Black Genius of Sonia Sanchez

While Sanchez now focuses on the struggle individuals endure trying to survive and search for love and joy in their lives, ever the activist and feminist, her work continues to advocate for revolutionary change.

We are indebted to Sonia Sanchez for reminding us that the Black voice is not a small voice, and we will always honor her as a profound voice, “initialed Black Genius”.

This Is Not a Small Voice

This is not a small voice

you hear this is a large

voice coming out of these cities.

This is the voice of LaTanya.

Kadesha. Shaniqua. This

is the voice of Antoine.

Darryl. Shaquille.

Running over waters

navigating the hallways

of our schools spilling out

on the corners of our cities and

no epitaphs spill out of their river mouths.

This is not a small love

you hear this is a large

love, a passion for kissing learning

on its face.

This is a love that crowns the feet with hands

that nourishes, conceives, feels the water sails

mends the children,

folds them inside our history where they

toast more than the flesh

where they suck the bones of the alphabet

and spit out closed vowels.

This is a love colored with iron and lace.

This is a love initialed Black Genius.

This is not a small voice

you hear.

– Sonia Sanchez, Wounded in the House of a Friend (1995). Source: Poets.org

About the author:

Karla Mendez (she/her) is currently an undergraduate student at the University of Central Florida, pursuing a major in Interdisciplinary Studies and a double minor in Political Science and Women’s and Gender Studies. She holds a certificate in Feminism and Social Justice from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and has just completed an internship with the United Nations Association. In addition to being a student, she is a freelance writer. Karla is of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent, she recognizes the importance of intersectionality in feminism, and as such, her research and writing focus on the intersection of race, gender, class, and politics.

With her writing and research, she wants to introduce people to historical figures who paved the way for change while bringing awareness to how discrimination and oppression can affect people differently. She will continue to explore her research as she begins graduate school next year to pursue a Master’s in Women’s Studies and American Studies. When she isn’t studying or reading for school, she enjoys reading for fun, watching old movies, and spending time with her family. You can follow her on Instagram.