Where Would Black Feminism Be Today If It Wasn’t For Barbara Smith?

Black feminist lesbian pioneer, activist, and organizer, Barbara Smith. Photo Credit: David Yellen.

By Jaimee A. Swift

A radical Black lesbian feminist activist icon, Barbara Smith laid a formidable blueprint and foundation to intersectional Black feminist thought and behavior. Black feminism would not be where it is today without the power of Smith’s work, leadership, and commitment to the liberation struggle.

Barbara Smith’s interview is a part of our March theme, “Sankofa: Honoring Our Black Feminist Pioneers.” To read the descriptor, click here.

“Unlike any other movement, Black feminism provides the theory that clarifies the nature of Black women’s experience, makes possible positive support from other Black women, and encourages political action that will change the very system that has put us down.”

Barbara Smith is most certainly an icon––a Black feminist icon. A prolific writer, educator, author, organizer, and socialist, Smith has been dedicated to the struggle for freedom since her teenage years; starting her organizing work in school desegregation during the Civil Rights Movement in her native Cleveland, Ohio. At age 73, Smith is still just as committed to dismantling oppressive systems and structures and in catalyzing coalitions and solidarities to create a world where people can truly be free.

Internationally recognized and known for her groundbreaking work in building, fostering, and sustaining Black feminism as a field, study, a theoretical framework, and political praxis, Smith is the co-founder of the Combahee River Collective, a Boston-based Black lesbian feminist and socialist organization established in 1974. Named after the Combahee Ferry Raid, a military operation led by freedom fighter, Harriet Tubman, along the Combahee River in South Carolina during the Civil War in 1863, members of the collective including Smith, her twin sister, Beverly Smith, and Demita Frazier, wrote and published one of the most important and significant Black feminist texts: the Combahee River Collective Statement. Stating that “the most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking”, the Combahee River Collective Statement ushered in a intersectional, radical Black feminist analysis that examined and emphasized the simultaneity of oppression in the experiences, perspectives, and identities of Black women. Moreover, the Combahee River Collective Statement has paved the way for what we know, understand, and interrogate as intersectional feminism.

In 1980, Smith, at the urging of her friend, Audre Lorde, co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first national publishing company run by and for women of color. Working in collaboration with countless feminist pioneers such Lorde, June Jordan, and Gloria Anzaldúa, Smith spearheaded and published works such as This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color; I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities; and Cuentos: Stories by Latinas. She also edited pioneering works such as Conditions Five: The Black Women’s Issue (1979) with Lorraine Bethel (which Smith’s trailblazing essay, “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism” was originally published and was later re-published in Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology); All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us are Brave: Black Women’s Studies (1982) with Akasha Gloria Hull and Patricia Bell-Scott; and Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, with the first edition published by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in 1983 and a second edition by Rutgers University Press in 2000.

Nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize and elected to the Albany, New York Common Council in 2005, Smith continues to lecture, politically organize, and speak out against social injustices such as war, colonialism, and racialized, gendered, and sexualized violence, imperialism, and more. Relentless and unwavering in her values and in the fight for the liberation of all marginalized peoples, Smith is most certainly the epitome and embodiment of what it means to be a Black Woman Radical.

Smith spoke with Black Women Radicals about how Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement shaped her activism; the best advice she received and what advice she would give to activists today; the importance of The Smith Caring Circle in supporting her life’s work; what a Black Woman Radical means to her; and more.

May you please share with me the moment or moments that led you into your activism?

Barbara Smith (BS): “I would say it wasn’t a moment but the historical period I was born into. I was born into Jim Crow––the last years of official Jim Crow. In some ways, of course, we know that Jim Crow never really ended but public restrictions around segregating institutions and facilities, that was very much in place when I was born in 1946. Because I was born in 1946, that meant I also was coming of age during the heights of the Civil Rights Movement. Unlike other eras when the political culture would not necessarily be as pervasive and as transformative as that period in mid-twentieth century U.S. history, my life just happened to coincide with that period. Whenever I talk about the fact I was politicized in the context of what was going on historically and politically, I always have to add that there are many people in my age group who are not political at all [Laughs]. Obviously, it wasn’t just the fact that I was growing up during Jim Crow and that the civil rights struggle was becoming ever more powerful and vibrant during those years. I think I always had a certain sense of injustice, which I always say children have because they are quick to say what is or is not fair; often, of course, out of self-interest!” [Laughs]

“Of course, my family was really conscious about the racial reality. Even though they did not emphasize the horrors they escaped by leaving rural Georgia and coming to Cleveland, Ohio, while they did not harp on those experiences, I feel like it was kind of by osmosis that I got a sense of what life was like for them in a very different place; living under the threat of incredible violence and second-class citizenship status. I actually became active politically during the Civil Rights Movement in Cleveland, which was focusing on school desegregation, as many of the Northern civil rights movements were. I recently found out by reading Jeanne Theoharris’ book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History, that when we were having our school boycotts in Cleveland and organizing around school desegregation, so were other cities. She writes specifically about New York City and Boston––two cities I’ve lived in.”

“In the 1960s, when the Civil Rights Movement was protesting and organizing around new public schools that were going to be built that would have maintained segregated enrollments, the people in the Civil Rights Movement made an effort to get kids involved. By that time, I was in high school and I was among the older cohort of students. We also had a civil rights martyr in Cleveland––Bruce Klunder––and he was protesting at one of the school’s construction site. He was behind a steam shovel and there were protesters in front of the steam shovel. The person who was operating the steam shovel backed up, thinking it was going to make it safer for the people who were in front but he immediately killed Bruce Klunder. Klunder was a minister, he was in his twenties, and he was White. That really catapulted the organizing to another level, as one would expect. There was a call for a school boycott in April 1964 and my sister [Beverly Smith] and I participated in the boycott. The Saturday before the boycott, there was a specific protest that was for youth. From that day to this, I have been politically committed and always wanting to engage in working for political change.”

When thinking about all the things you have done in regards to your activism and leadership, what would you say you are most proud of?

BS: “I will say two things. One, is the concept of making a way out of no way. From this vantage point, as an elder and looking back on the things I have done with my life, I feel like I often was in the position of, ‘Oh, we don’t have that but we need to have that, let’s make that [and] create that.’ [Laughs] That is true of Black feminism. That is true of Black Women’s Studies. That is true of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. I am proud of the fact I wanted to be involved in building opportunities, building content, and building political organizing and movement that did not exist in the same way previously. I feel good about that. I also feel good about the fact that I am a part of the Left. I am a Democratic Socialist and have been engaged in radical political work throughout a lifetime. Most people don’t necessarily know what one means by radical––they think radical means violent, disruptive, attacking, and all kinds of things that radical doesn’t necessarily mean. Radical means going to the root. Ella Baker was a radical but radical doesn’t necessarily mean flame throwing. In fact, one of the best ways to be a radical is not to be a flame thrower [Laughs]––it is to be effective enough in one’s means and [effective in] ways of communicating to get your ideas and agendas implemented. I am very proud of being a part of the Left in the United States.”

“I am proud of the fact that I wanted to be involved in building opportunities, building content, and building political organizing and movement that did not exist in the same way previously.”

You co-founded the Combahee River Collective. You were also one of three authors––including your sister, Beverly Smith and Demita Frazier––of the Combahee River Collective Statement. Looking back when you were organizing, did you think you would have such an impact on Black feminist thought and behavior? How does it feel to hear that your work has transformed people’s lives and politics?

BS: “I don’t think there was anyway we could have known we were going to have the impact we did. We were a local organization doing work with other people in a coalition and [we were] just trying to address the issues that were coming at us thick and fast as Black women [and] in most cases, as out lesbians living in a cauldron of racism which is Boston. The fact that Combahee was started in the context of a race war in Boston around school desegregation––I don’t think people should forget that. How amazing that a group of Black women could come together to build multi-issued politics in a situation where Black people and the White power structure was about the opposite? There was no way we could have known we would have that level of impact. If we had not written the Combahee River Collective Statement, I don’t think anyone would have known about us, at least not to the same degree. That statement is what really leveraged us into history, so to speak.”

“One of things about the [Combahee River Collective Statement] is it is true today just as the day it was written. As a literature person, there is the concept of classics and what makes something a classic. One of the things that makes something a classic is it stands the test of time. It makes me very gratified that the Combahee River Collective Statement is in many ways a political classic because it is just as useful today as the day it was written. It also shows the depth of our political analysis. I often say the fact we had a socialist and anti-capitalist analysis combined with our Black feminist, anti-patriarchal, and anti-racist perspective was like, ‘how unstoppable is that?’ because we were hitting all cylinders. We say in the Combahee River Collective Statement that ‘if Black women were free, then everyone else would have to be’ because we experience all the oppressions.”

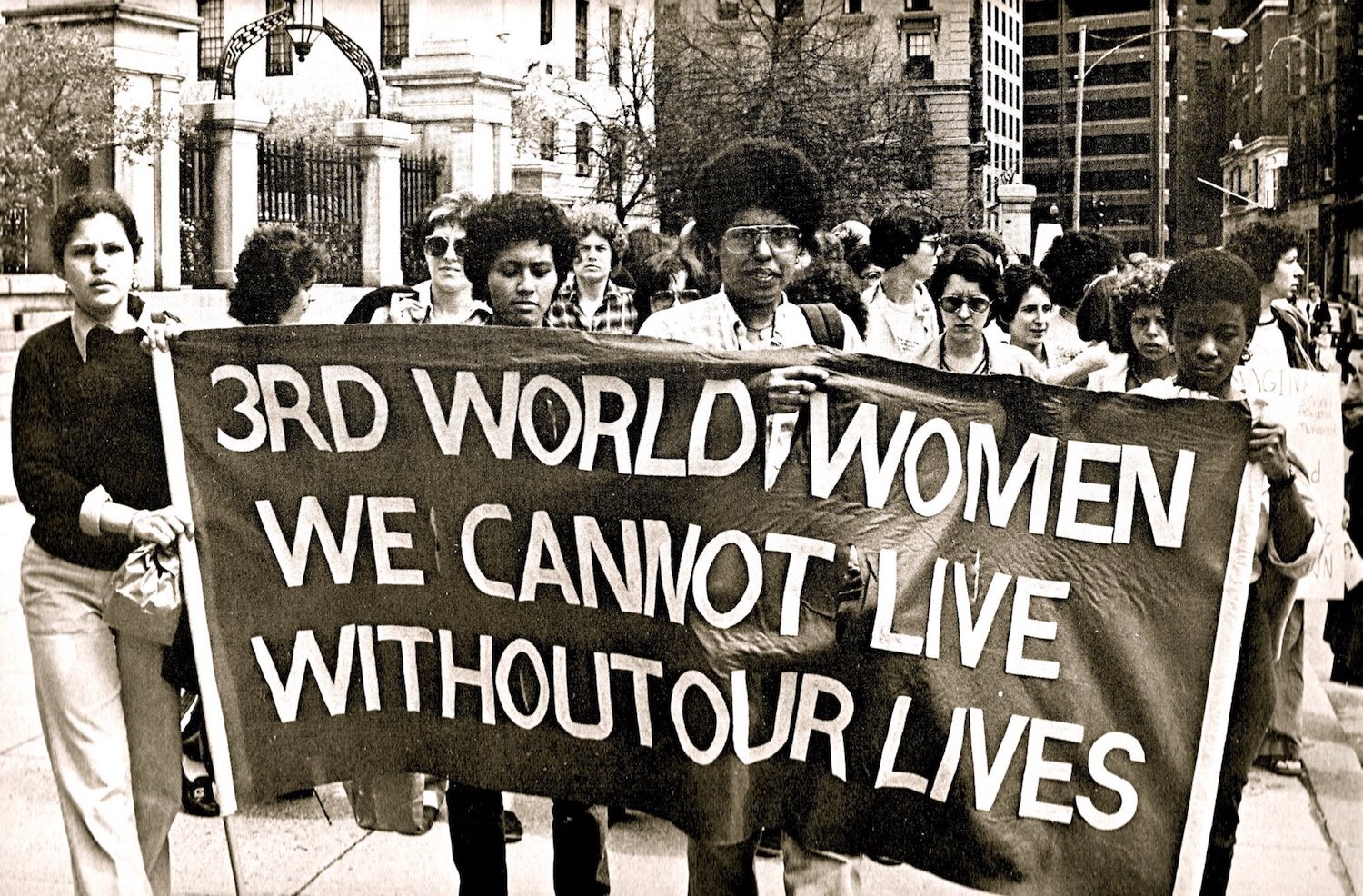

Members of the Combahee River Collective (far left to right) Maria Elena Gonzales, Margo Okasawa-Rey, Barbara Smith, and Demita Frazier, at a protest against violence and murders of Black women in Boston. Photo Credit: Tia Cross.

“It feels great, of course, to hear I have inspired people! [Laughs]. The things I have been able to do, I consider it to be a privilege to have been involved in struggle. I consider it a privilege to have had the leeway in my life and sow the skills that could make the things I pursued possible to accomplish. The fact that I had such a great education, starting at home and starting at kindergarten; our family was all about that. My sister, Beverly, who is one of the co-authors of the Combahee River Collective Statement, she talked about how religion and education were the twin pillars in our home and she’s right. We were really fortunate we were oriented toward doing rigorous academic and intellectual work. However, at the time, it was ‘get your school work done, it is important’ or ‘do what your teacher says.’ [Laughs] Those were the perfect building blocks and perfect context for me to be able to do some of the things I dreamed about doing. I always wanted to be a writer––that was my dream. The level of literacy that was nurtured in us [and] the love of books that our family shared, those were all building blocks for being able to create some of these things.”

“One of things about the [Combahee River Collective Statement] is it is true today just as the day it was written. As a literature person, there is the concept of classics and what makes something a classic. One of the things that makes something a classic is it stands the test of time. It makes me very gratified that the Combahee River Collective Statement is in many ways a political classic because it is just as useful today as the day it was written.”

“People often asked if my family was politically active and I think in a conventional sense, the answer would be yes and no. They were not a part of movement organizations but they paid very close attention to the Civil Rights Movement because they were from the South. My sister and I were the only Northerners in our house and virtually, the only Northerners in the family; well, maybe except for our cousins who were in our age group. [Laughs] Our family were all Southerners due to the Great Migration, of course, and were transplants of the Great Migration. They were very politically conscious and they were Black-identified, I would say. Our grandmother would work at the polls whenever there was an election. There was a neighborhood association and [our grandmother] was also involved with that. Our church was very involved in political issues because the minister was one of the most prominent Black leaders in Cleveland and our church was considered to be one of the prominent churches, which I didn’t know that at that time. At home, at church, in the neighborhood and in the community––those were the influences that made so much possible.”

Do you have any solidifying moments/memories in regards to your organizing and activism, that stand out?

BS: “I think the most dynamic organizing we did while we were involved with Combahee was when 12 Black women were murdered in Boston in a four-month period in 1979. That was kind of the pinnacle I think of what our collective work and political analysis and praxis was with that situation. It is hard to use the word favorite on something so tragic and dire but it certainly was a culmination of all that we tried to accomplish and all we had put into existence. We were kind of the point people for all the organizing in Boston during that period, for several reasons. One is that we were already politically active. We were aware there was such a thing as violence against women and we were not fools into thinking that the reasons these murders were happening solely were because of racism––even though we were in a racist cauldron, as I had said before. In other words, we had a way of looking and understanding the murders that was highly useful and totally relevant to what was going on because if there were only racial murders, it would seem to me that some Black males would have been murdered as well. Also, we had connections to the Women’s Movement and the feminist community, where there were resources and organizations that were addressing violence against women across racial identities. There was a battered women’s shelter called the Transition House that had recently started in Cambridge––it was the second one to open in the entire nation. There were organizations that had been formed for the purpose to address the issues of violence against women and we had the connections to those organizations. We also had connections to the Black and Latino and Latina communities, so we were in a good position to be and work with those people. That was the most powerful organizing I have been involved in.”

These pamphlets were created by the Combahee River Collective as a campaign to bring awareness to the murders of Black women in Boston. They updated the pamphlets as the deaths of Black women increased. Photo credit: wbur.org

“We built powerful coalitions that had lasting impact on the political culture of Boston. One of the things about that organizing is that I think a lot of people, even today, do not know what Black feminism really is. There are so many misunderstandings of what that looks like. I get highly disturbed at what I see is being portrayed as Black feminism on social media because it is certainly not what we were about. Be that as it may, when you can say to people, ‘Yeah, we were organizing because 12 Black women were killed’, you should pause for a moment and say, ‘Wow, this is really serious.’ This is not frivolous and this is not identity politics mis-defined because we can talk about what we meant by identity politics versus what everybody else thinks it is. I think people need to take the work seriously. Some people need to understand the depth of what we were up against, what we were fighting, what we were committed to changing, and the type of liberation we wished to accomplish. And we haven’t accomplished that yet––women are still being murdered, women of all different identities. So, we haven’t accomplished that yet but certainly it was our goal to bring attention to violence against women and to change perspectives on what is alright and what is not alright in regards to how we get treated. There has been a continuum of violence and sexual stereotyping, exploitation, harassment, battering, and murder. Us organizing around murder means we were encompassing the rest of that, too.”

May you please share and describe the process of creating and starting Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press and curating and editing the book, Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology and the feelings you had when it was published?

BS: “What is important about Home Girls was it was my efforts to preserve Conditions: The Black Women's Issue (1979). It is very important to understand that. Home Girls was not a thing in itself–it was a continuum of work of “Toward A Black Feminist Criticism”; Conditions Five: The Black Women’s Issue, and [then] Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology. Of course, I was thrilled the book was published and without Kitchen Table, it would have never been published. It was supposed to be published by a White lesbian feminist press, Persephone Press, and they decided to go bankrupt six weeks before my book was to be released. So, if it were not for Kitchen Table, that book would have never been published because who else would have wanted it? I guess another White women’s press, maybe [Laughs]. That would have been my alternative. I would have had to find another feminist press because no mainstream press would never published such a book back then. Fortunately, we started Kitchen Table and I had a place to take the book to. I was afraid my book was never going to be published. Fortunately, I have a dear friend who I went to college with who was an attorney and she was the one who helped me get my book back. You see, they had already done full production on the book. The book had been typeset and the cover had been designed. If we had not gotten that material content from the book back, we would have had to start the book from scratch and typeset it. Of course, in those days, there was no desktop and typesetting was a very expensive process. It would have been a nightmare.”

“One of the things about that organizing is that I think a lot of people even today do not know what Black feminism really is.”

“Fortunately, she helped me get the material remains of my book back, which as I said, was only a few weeks away from being printed. That was quite wonderful. The press I mentioned, Persephone Press, was in the Boston area, and I literally brought my book, Home Girls, back to New York City in shopping bags. I am talking about the page proofs! [Laughs] So, I was delighted to have Home Girls come out! [Laughs] I still have the first copy of Home Girls that came out of the box. It is a little battered now because it is the copy I always took with me to do presentations but I still have it. I will tell you a few things about Home Girls as an entity. You asked me about the editing process and I don't even want to talk about that because I don't really like editing! [Laughs]. Conceptualizing the book was more interesting, especially the title. No one was using the term, ‘home girls’ in the early eighties––no one. Everyone was talking about ‘home boys.’ Hip-hop culture, which at the time was rap, was just getting started. People were talking about ‘home boys’ and it was very New York. I started thinking, ‘Well, yeah, what about home girls?’ That is what the book is!” [Laughs].

Cover of the first edition of Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (1983).

“My sister Beverly and I were talking about a title of another one of my books and there was a persuasion process I was having about a title with another person and she said, ‘Why would anyone think they could give a better title than you?’ [Laughs]. She said, ‘You are a master of coming up with titles.’ This seems to be true because I was the one who came up with the title, All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women Studies. Yes, that was my title! I know how to do titles [Laughs]. The thing is, if you have a good title, you understand your book better and you understand what you are trying to do. I used to use that title, All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave, long before the book. I was being asked to do presentations on Black Women’s Studies and Black women’s literature. So that was the title I would use during talks about the work I was doing in the early days working in Black women’s literature and Black Women’s Studies. Now getting that title was a battle royale––I had to fight for that one.”

“Physically, I wanted the book to look like Alain Locke’s The New Negro. When you look at The New Negro and then at Home Girls, you will see I was influenced by it and I wanted the work to have those elements such as beautiful black and white graphics. The original cover of Home Girls is African textile design. I wanted the book to be understood as a part of Black and by extension, African culture. The graphics in the book are African design as well. That was a way of saying, ‘Yeah, you say we are not a part of the race because we are not heterosexual and we do not qualify on the scale of heterosexual, and therefore, we are not Black.’ That was a very common perspective back then. It is still a perspective now––if you are not straight, you are not a Black person. Go figure. In any event, the visual design of the book was my way of saying, ‘Yeah, guess what? This is a Black thing.’ [Laughs] Home Girls was also the first book to have the words ‘Black feminist’ on the cover. This is similar to Some of Us Were Brave because it was the first book to have Black Women’s Studies on the cover. Nothing predates it. I feel good about that.”

What is the best advice anyone has given you?

BS: “The best piece of advice I was given was during the Kitchen Table years and this wonderful person, who was actually old enough to be my mother––she actually could have been my mother. She was in her seventies and I, in my forties, at that time. After an unfortunate circumstance dealing with the press, she said to me, ‘You don’t have to tell everybody everything.’ What she was basically saying was be strategic: everybody doesn't need to know all of your business. She was saying on a strategic level, people cannot use stuff to hurt you if they do not have the information. I thought that was really good advice. I am not sure if it is useful for anyone else but it certainly taught me about how to be strategic in communication, which I always tried to be.”

“After an unfortunate circumstance dealing with the press, she said to me, ‘You don’t have to tell everybody everything.’ What she was basically saying was be strategic: everybody doesn’t need to know all of your business. She was saying on a strategic level, people cannot use stuff to hurt you if they do not have the information.”

“My mother, who died when I was nine so I barely knew her, she told my sister and me one night after our aunt gave a present we were not excited about––she was not happy with us––[but] she said, ‘You can catch more flies with honey than you can with vinegar.’ Of course, we had no idea what she was talking about! [Laughs] But we certainly got the point that we did not seem appropriately appreciative of this gift. I have thought about that and quoted that many times. I think it is a very good way to proceed in the world. You don’t have to be cruel or mean or have to yell or have to insult; you don’t have to do any of those things. You don’t have to be mean or negative with confrontation. You can actually say exactly what you wish to say for people to consider without being caustic or insulting. I think that was a great piece of advice. It is probably the best piece of advice––my mother first and then what my dear friend, Lucretia Diggs, said.”

Beverly Smith, Kate Rushin, and Beverly Smith with This Bridge Called My Back contributors and editors Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa (back row). Photo: Twitter via Well-Read Black Girl.

What advice would you give activists today?

BS: “Do some activism. Most people don’t really understand what it means to be involved in activism and political organizing. Some of these people on social media, what they are doing is not activism. Putting people down in a virtual medium or either in person––which connects what I was saying about my mother’s advice––that is not activism or organizing. Organizing is strategic work that should be motivated by a deep passion for wanting things to be different. I just saw the film, Just Mercy, and one of the things that film shows is: what do you do to change a situation when it looks like other people have all the cards? What you see is Bryan Stevenson just keeping at it. It is painstaking, day-by day work.”

“Do some activism. Most people don’t really understand what it means to be involved in activism and political organizing. Some of these people on social media what they are doing is not activism.”

“Right now I am involved with helping to organize a demonstration to stop war against Iran. Some of us have done this countless times before, so we have a sense of what the steps are but it is very precise work. You really have to believe in what it is you are doing. We can take a problem or a situation that is more ongoing––let’s take violence against women for example. What do you do on a daily basis to change the reality of violence against women? How do you organize around that? I know people like Beth Richie who have been involved with the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence since the 1980s. It is day after day, very strategic and conscious work. I love strategizing. I love flying in the face of what the power structure thinks is my lot in life. As soon as I figured out what the power structure thought was my lot in life, I wanted to alter that [Laughs].

May you please speak more about The Smith Caring Circle and the importance of the Circle in supporting your work?

BS: “The Smith Caring Circle is what allowed me to retire at the age of 71. I had a day job up until the age of 71 because I did not have the wherewithal to retire. It is not so much how The Smith Caring Circle supports my work because that sounds like it is a fellowship or something [Laughs]. I am a worker. I was put on here on this earth to work for change and I don’t mind that. [The Circle] is not so much supporting my work but supporting my life. It gave me enough to actually not go to the day job any longer. That is what The Smith Caring Circle has done for me. It has allowed me to write a few things that I probably would have said no to. I co-taught a course at my alma mater, Mount Holyoke, this fall on Black women activists. I could not have done that if I was still going to the day job.”

“I cannot tell you how appreciative I am and how gratified I am that there are people who wish to see me be able to have the kind of retirement all of us deserve and look forward to. I always prioritized the struggle. Doing things like Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, I did not have the kind of retirement resources like those who made different choices. This is a realization that the work I have committed myself to, often without compensation and certainly without pension, this is a recognition of that. It feels really beautiful that people have stepped up and are stepping up.”

Barbara Smith at a protest. Photo Courtesy of Barbara Smith.

What does a Black Woman Radical mean to you? Who are some Black women that inspire you?

BS: “Being a Black Woman Radical means that you have a political practice. It means you don’t just read about the issues and talk intelligently about them. Many people are very alert to how the systems of oppressions, of power, and control that exist are not in our favor. Many people know about these things and are upset about it, too. They can talk very engagingly about the kind of things that happen. You can talk about being a woman of color, about being in the LGBTQIA community, and we can talk engagingly about what that is like and how oppressions manifest against us. But a Black Woman Radical is doing something about it.”

“Being a Black Woman Radical means that you have a political practice. It means you don’t just read about the issues and talk intelligently about them.”

“We have great examples in our history of people who did the work and who are still doing the work. I just read Angela Davis’ collection of interviews and essays, Freedom Is A Constant Struggle. One of the questions I asked a friend was––my friend and I started a study group last summer and it is our hope we are building activists and organizers through having this study group. We read the book and one of the questions I asked during the study group was, ‘What kind of person is Angela Davis? What are her values and what kind of person is she that she can be an organizer from probably her teenage years until today?’ What is up with that? What kind of person is that?’ She is a Black woman who inspires me. I think about Assata Shakur, Audre Lorde, and Lorraine Hansberry. Pat Parker’s name is not mentioned as often but Pat Parker was an incredible person and an incredible writer, and I would also say she was a Black Woman Radical. Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker, too.”

Support Barbara Smith by becoming a monthly donor at The Smith Caring Circle.

You can follow Barbara Smith on Twitter.